“what is man? a poetic meditation on a sci-fi story”

I remember how, after watching Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (synopsis; trailer; cast & crew) for the first time (many years ago), it left me (and I left it) with a slight feeling of incomprehension. But I also remember that I enjoyed a lot – and still do, after my most recent viewing of the movie – the “tools” that Tarkovsky uses to create a futuristic (and, at times, fantastic) world. I am referring here to the use of mid-twentieth century environs and objects (brutalist architecture; concrete tunnels and suspended highways; or the cars of the moment, but with added antennae, and with modified sound etc.); to the choice of filming certain “common” materials and surfaces in such a way, that they can “stand in” for environments and places in the movie (e.g. the close filming of various liquids or of smoke, to create the impression of the Okean – the ocean – of Solaris); and to Tarkovsky (and his cinematographer) using practical and in-camera effects to give the impression of different situations or states of being. The research station itself, in fact, is a good example of how to use available and less-expensive props, to construct a futuristic, even a bit alien, environment – and doing that with creativity and charm (even if the “seams” are sometimes visible). Yes, I liked these aspects when I first saw the movie – and I still like them now; but, returning to my initial point, if last time I saw the movie I left with a slight feeling of incomprehension, what is the situation now, after my most recent viewing of the film? Do I understand Solaris, now? Or, more importantly – what kind of “understanding” are we talking about – or should we be talking about, in fact?

I remember how, after watching Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (synopsis; trailer; cast & crew) for the first time (many years ago), it left me (and I left it) with a slight feeling of incomprehension. But I also remember that I enjoyed a lot – and still do, after my most recent viewing of the movie – the “tools” that Tarkovsky uses to create a futuristic (and, at times, fantastic) world. I am referring here to the use of mid-twentieth century environs and objects (brutalist architecture; concrete tunnels and suspended highways; or the cars of the moment, but with added antennae, and with modified sound etc.); to the choice of filming certain “common” materials and surfaces in such a way, that they can “stand in” for environments and places in the movie (e.g. the close filming of various liquids or of smoke, to create the impression of the Okean – the ocean – of Solaris); and to Tarkovsky (and his cinematographer) using practical and in-camera effects to give the impression of different situations or states of being. The research station itself, in fact, is a good example of how to use available and less-expensive props, to construct a futuristic, even a bit alien, environment – and doing that with creativity and charm (even if the “seams” are sometimes visible). Yes, I liked these aspects when I first saw the movie – and I still like them now; but, returning to my initial point, if last time I saw the movie I left with a slight feeling of incomprehension, what is the situation now, after my most recent viewing of the film? Do I understand Solaris, now? Or, more importantly – what kind of “understanding” are we talking about – or should we be talking about, in fact?

Well, the kind of “understanding” with which I prefer to approach the meeting with a piece of art – and that yields the richest fruits, from that meeting – is (as I mentioned elsewhere) not a rationalistic, “puzzle-solving” one. In fact, I am acutely bored by works that offer – or even demand – only that sort of “understanding”. And I think that the very problem with my initial encounter with Solaris, and part of the reason why I left (almost) empty-handed, that time, was that I was inherently looking for a “rational” interpretation and comprehension of the work, being trained to do so, by previous viewings of works from the “sci-fi” genre (and whether or not this movie can even be categorized within that genre is yet another discussion). For my most recent viewing of the film, however, I adopted (with more courage, I would say, but almost unawares, or in a natural way) another approach – which is the one that I prefer, by the way; and I could call this approach “poetic-lyrical”, or one in which I allow the piece of art to have its emotional-existential impact on me, without forcing a rational, puzzle-solving interpretive key on it. And you can read more about the results of this specific encounter in what follows:

Thus, the main “result” of the encounter – the principal imprint that the movie left on me – is the feeling that I had just been engaged in a meditation on what it means to be human; a meditation of a poetic-lyrical, and philosophical, and existential kind – and endeavored using the framework of a sci-fi story. A lyrical-philosophical meditation, then, and not the meditation of an “accountant” – which is what Kris Kelvin, our main protagonist, starts out as being. “Accountant” understood figuratively, of course – because Kelvin is, in fact, a scientist; a psychologist, even; but a kind of scientist (who pursues the kind of science) that might represent one of the sad and barren, blind alleys of modernity. In other words, pursuing not the science of “wonderment”, which is eager to search and to discover the human beings – or beings, in general – as and how and where they are; one that is open to being surprised, even overwhelmed, by what it discovers; and one that “reads” reality with all the capacities of understanding and feeling of the human being; no, but a reductionist kind of science, of algorithms and formulae, of reducing reality to what can be quantified and measured; a “science” that in effects blinds the researcher to the fullness of reality, and which yields no meaningful results – about beings; and an approach that, it turns out, is actually inhuman, and thus not fit to understand human beings – or other beings. And Kris Kelvin’s father, Nik, tells “us” these things, that his son has an “accountant’s” approach, right at the beginning of the movie – but we connect the dots only later, realizing also why there is, seemingly, a deep and entrenched mis-understanding, lack of communication, distance, or gap, between Kris and his father. And later we also realize that right at the beginning of the film we were shown the ways in which the father is so different from his son – see his house, which is a re-construction of an “old” (i.e. twentieth century) house, and which is filled with the artefacts of human culture (books, paintings, busts) – i.e. of humanity. Kris, meanwhile, while living at the same place, is instead consumed by his “dry” work – and he even has to be forced by the father to take a break every day, to go out and to walk through (and to gaze at) nature. Because, as Kris himself tells us (with quite some pride), he “is no poet”; instead, he is “interested in the truth” – but a truth as confined by the limits of his “accountant-like” scientific understanding.

And yet all of this will change, brusquely and radically, once Kris gets to the research station that hovers above the surface of Solaris, this planet that had remained “impenetrable” (in terms of being able to dissect it with the tools of rationalistic science) for the human beings, for so many decades – so much so that they are now considering shutting down the entire research station on Solaris (and/or resorting to the most violent means of “science”). What takes place, then, with Kris Kelvin, on (or, rather, above) Solaris, is a sort of “conversion” – from “accountant”, to full human being. And, interestingly enough, it is in and through the encounter with an alien “thing” – with the Okean (this “thing” that seems to be able to perceive, and then to physically manifest, the content of these human beings’ psyche, or consciousness, or selves) – that Kris, and perhaps the other scientists, will re-learn (or maybe learn for the very first time) how to be human.

I really liked the Okean – this ocean on the surface of Solaris, which appears to be a “being”, or ”thing”, of a raw emotional nature; and whom, in consequence, the humans have been unable to “understand” or to communicate with, using the tools of reductionist science; but who will be “tamed” eventually (and with whom contact will actually be made) when it will be given access, finally, to the very raw “selves” of the human beings (by transmitting to it Kris Kelvin’s electroencephalogram); yes, only then true communication will be achieved between this raw emotional self that seems to be the Okean – and the raw and true human selves of the human beings. Because the Okean had been trying to communicate with the human beings, consistently and from the beginning, but only within the bounds and through the means of its own “natural” possibilities – i.e. by replicating (in physical form, through real embodiments) the content of the inner selves of the researchers (and in the process driving some of them almost mad, or at least puzzling them to no end, given that their reductionist scientific paradigms could not even begin to make sense of these… “hallucinations” that were flesh-and-bones).

Indeed, what happens when a civilization that has apparently lost the capacity of being fully human, and that becomes limited (at least in regards to its decision-making) to rationalistic, quantitative, reductionist thinking – what happens when this civilization, through its “scientific” vanguard, meets a being that is only, and purely, an emotional self – and that therefore can only communicate in those terms, and only with the raw human selves? Well, in the movie this had lead, as said, to decades upon decades of in- or mis-communication, and almost to a final disaster -– until the humans succeeded (almost by chance) in finding a way to connect; that is, until they, the human beings themselves, re-discovered their own selves , which then allowed them to communicate that very self to the raw, emotional self of the Okean.

But, getting back to Kris Kelvin’s “conversion”, or transformation, I would have liked for the emotional violence of the initial shock to be portrayed more visibly, more powerfully – and this remark touches in fact on a certain formalism that characterizes (to a certaibn degree) the acting style employed in many of Tarkovsky’s movies (which I do not find appealing – but which I eventually learned to accept as a stylistic feature, or as a specific idiom, within this cinematic universe). Yet the reason why I would have liked a more “violent” depiction of the initial shock underwent by Kris, is that this shock will be the main catalyst of Kris’ thoroughgoing, deep transformation, which will take place throughout the rest of the movie. I am referring, of course, to the initial, self-shattering shock of seeing his wife (who had been dead for ten years) be materialized next to him – and, as it turns out, out of him (his psyche). His wife, who had committed suicide ten years earlier, because she had realized that Kris could never actually love her, nor give himself fully to her – because his work (his dry, rational work) was his true love, and always came first for him, as a matter of an intentional and conscious choice. But not anymore, but not now – because the festering wound that seems to have lurked at the heart of Kris’ self will now produce, through the mediation of the Okean, a being (Khari, or Hari), who is… his wife, “re-born”; and who will soon become, as Kris says, “worth more to me than science can ever be”. And these feelings will remain even as Kris realizes and knows (leading, initially, to attempts to physically get rid of this Khari) that she is a materialization from and by the Okean; but also that she is, otherwise, and in fact, very real indeed: flesh and blood, and true self, and true emotion – i.e. with the emotional rawness and reality of his (ex-)wife. One can even say that Kris accepts this Khari’s “otherness” (that she is, as a “being”, distinct from his dead wife) and yet that he loves her, nonetheless – and even (perhaps) because of and through that.

And what a lovely and moving “being” is “embodied” by the Okean – a being that, although made by the Okean, and reflecting Kris’ psyche, is autonomous and independent from the Okean, in terms of her self-awareness (even if she can never physically leave Solaris) – and which is also desperately “not” autonomous, and literally unable to live without, or even far away from, Kris (any attempt at physical separation leading to very violent and harmful consequences for her). But she is real, yes – and very real for Kris, as well; perhaps even more real than his previous wife; because the relationship that they develop (Kris and this Khari) is itself real and emotional and powerful and close – and probably more powerful than the “original” relationship ever was. But this Khari, having an autonomous consciousness, will end up (sadly, again) being driven to despair by the realization of the fact that she is not, and can never be, the “original” – and seemingly also by the fact that she simply can not believe that Kris will ever be capable of loving her, truly (!) – given that she is not the “original”. (But I confess that this aspect, of the reasons why this Okean-born-Khari succumbs to despair, is one that I did not fully “understand” – in terms of a full and rational comprehension of the motives.)

But Khari – while ever so lovable and fragile and beautiful (as portrayed by Natalya Bondarchuk) – and while so important for the change that Kris undergoes – is not, however, the central theme of the movie (although she is its central “mechanism”, and where its “heart” beats, or starts beating). The theme of the movie, instead – its core subject – seems to be “the discovery of humankind” – in the ironic context of the fact that they (we) have to go to a different planet, and encounter an alien “being”, in order to discover (again) what it is to be human.

“Being human” – a condition whose artefacts are strewn throughout the movie: from Nik Kelvin’s house, as mentioned; to the “library” on the station, which is also their main meeting place; to conversations between the scientists (with running references to Don Quixote, Tolstoy, Faust, Dostoevsky, and the like); to the classical music that plays on the soundtrack (Bach, of course – and others); to the paintings (e.g. the gregarious Brueghel; or Andrei Rublev’s icon of the Trinity, used in a nice act of cinematic self-reference); to the busts of philosophers and to primitive art; and even to certain artefacts of science itself (e.g. a model of the human body). All these are manifestations of what it means to “be human” in a way so much richer, and broader, and more complex, than what an accountant-like, reductionistic approach, could ever begin to fathom and to understand (and, remember, Kris is supposed to be a … psychologist; that is, a knower of the human psyche – task at which he fails miserably, both as an “accountant”, and as someone who has no real understanding and awareness of the content of his own self).

And here we can recall how Kris dismissed the witness of one of the first people who had engaged with the Okean, Berton – how he brushed away his testimony as “scientifically nonsensical” talk of the “soul” and the like etc. In this sense, Kris’ path to becoming fully human is also a path that leads to the (re)discovery of a broader way of doing “science”, of a broader kind of “understanding” – one driven by wonder, and one that is fully open to being, to reality (instead of shutting itself up to it, in the name of – and by virtue of – its narrow-reductionist instruments).

And his trajectory of transformation will also take Kris Kelvin from being a thwarted, wounded, internally-warped human being – to being healed, to becoming fully human. And perhaps this is the meaning of the last scenes of the movie, as well – scenes that, it turns out, are actually a materialization from the Okean, reflecting presumably Kris’ psyche – and in which Kris Kelvin, who in reality decided to remain indefinitely on the Solaris station, gets to reconcile with his father, at his father’s house (a father who, as said, seems to embody or represent a fuller understanding and existential expression of humanity). And this reconciliation also seems to embody, symbolically and factually, the inner healing of Kris’ self; him becoming fully human.

Having said all this about the “story” of the movie, about what “happens” in it, let me now remark on a realization that struck me quite powerfully, while watching the movie – namely, of what I would call Tarkovsky’s “courage to make high art”; a courage that, to put it quite bluntly, I would be hard pressed to find in any (really, in any) of today’s film directors (well, Sophia Coppola might come to mind, as an exception from that, and regarding certain aspects of her work). I am referring to the fact that Tarkovsky dares to “speak” the language of high art; and to speak about and to make direct reference to high art; and to say important things, about the most essential dimension of the human existence; and to say all this in a strikingly beautiful manner. For example, even daring to ask “what it means to be a human being” – and to use the language and the artefacts of the accumulated human civilization to address this – is a feature hardly encountered either in film, or in art, more generally. Who does this anymore – in a veritable, genuine, truly artistic manner? But perhaps this dearth of real art and real humanity only confirms the core message of the film – about our modern age’s cultural reductionism, and about the subsequent loss of humanity, which follows in its footsteps; because, indeed, we seem to live that kind of impoverished existence, and to feel its consequences in art, in science, and in the types of “understanding” that are deemed acceptable in our times. (And when I refer to Tarkovsky’s “courage to make high art”, this does not mean some empty, pompous, formal, snobbish references to “Western civilization”, or to “Culture”; something like building in “Gothic” style, in the twenty-first century, in an act of meaningless and inauthentic imitation; no, I am referring instead to the courage of asking the essential questions – and of knowing, engaging, and being able to enter into a dialogue with, the answers that the human beings have given to these question throughout their history, throughout civilization; and to being able to speak the language of “human civilization”, naturally, with ease, and at the highest level.)

But experiencing Tarkovsky’s “courage to make high art” can also act encouragingly with regards to our own internal (artistic) cowardice, cowardice into which we might have been cowed as a result of being surrounded, overwhelmed even, by tremendously unambitious, mediocre, low-aiming “artistic” endeavors – and because one is not sure if there is even a public, anymore, who would be interested in hearing, let alone be able to engage with and to understand, such an (high, ambitious, meaningful) artistic language.

Another aspect that struck me about the movie Solaris – an aspect that “lingers” throughout the movie, appearing in flashes and brushstrokes – is “beauty” itself; its presence, in many different forms – its daring and comforting presence. Beauty being – we realize, now – another essential (and unique) manifestation of being human, of a full and true humanity.

A few more remarks – bits and pieces – about particular aspects or moments that have caught my attention; for example, the presence of a horse, which is one of the leitmotifs of Tarkovsky’s movies – and who, for me, represents the artist (as an instinctive, emotional, free, unruly, yet beautiful being; who is naturally what he is, and can only be what it is). (Indeed, an artist is like a bird – and “a bird can but sing”, because that is its nature; as explained in the movie The Lives of Others, by an officer of the secret police, the found out that breaking the “bird’s capacity to “sing” is the most effective and definitive way of breaking its very being.)

As I mentioned above, I also liked the fact that the Okean is portrayed as such a raw, emotional being – and also the fact that the woman, Khari, is also portrayed as an essentially emotional being – and frail, vulnerable, and very lovable, because of that; a kind of portrayal that, again, few would have the courage to pursue, today (but here, again, we are talking about the courage to make art; and what is art if not the expression of truth, as it is, where it is, and how it is?).

Let me conclude with a quote, whose exact spot in the movie I can not recall (but which must be from one of the many conversations between Snaut and Kris) – something about “the mysteries of happiness, death and love” – because it seems to encapsulate quite aptly the richness of a true (artistic, lyrical-poetic, wonder-driven, fully human) understanding of what is a human being.

And let me conclude with a question, as well: namely, whether Andrei Tarkovsky is one of the last exponents of this classical understanding – or, one could say, this understanding cultivated within Western civilization – of what is a human being.

And let me also conclude by attempting to answer my initial question, which started this discussion – namely, whether I “understand” the movie Solaris, now, after my most recent viewing of it. In order to answer this question, I will make a reference to what the movie itself seems to teach us – namely, that the only possible approach to grasping the fully human, is one that is driven by wonder, and that is characterized by an openness to the entirety of the human experience – including its past expressions. And art – according to a long-standing convictions of mine – is the branch of “knowledge” or human expression that is most adept, naturally, to reflecting the fullness of the human experience (while being informed by the other branches of knowledge, in a broad-humanistic vein). In other words, that (although this might sound like a tautology) the only possible approach to art, to poetry – is an artistic, or poetic, approach; meaning that a rationalistic, puzzle-solving approach will be inherently reductionist, and will thus result in an impoverished understanding – or in a mis-understanding – or a complete lack of understanding, and of communication (see Nik and Kris). So perhaps my first reading of the movie was (involuntarily) closer to an accountant’s (I repeat, involuntarily – because of being acculturated, by so many movies within the “genre”, to read them in a certain key, that tries to extract a meaning and a rational conclusion) – while my most recent one was maybe closer to a truly artistic (i.e. poetic, i.e. closer to the fully human) one.

In addition, one should also note that Tarkovsky’s cinematic language is irremediably (and beautifully, and happily so) lyrical (poetic) – which means that his movies can only be truly approached, read, and engaged, in a lyrical (poetic) key. Which is one of the reasons why Tarkovsky is one of my favorite directors in the history of cinema.

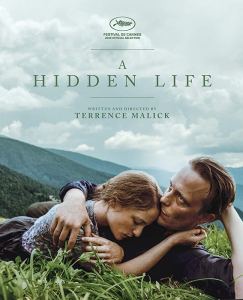

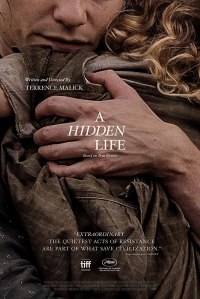

Soon after beginning Terrence Malick’s newest film, A Hidden Life (

Soon after beginning Terrence Malick’s newest film, A Hidden Life ( Because, how does one get to identify oneself with characters and situations – with the story – in a movie? Since we spectators are not actually there and then, we need to do it vicariously – and that happens when we, spectators, allow ourselves to become enmeshed in a given emotional, human situation; when we feel that it is us who are addressed by a character, in a dialogue – and we instinctively react to that, emotionally – and then compare our own reactions to that of the character addressed in the movie. In other words, it is through vicariously lived (“real” – that is, flowing, dynamic) human interactions that we are drawn in, into the given drama. And this is why it seems to me that this strange editing technique, by fragmenting and by making the characters’ interactions impersonal – also leaves us, to a good degree, emotionally outside – and contributes to the general feeling of “impersonality”.

Because, how does one get to identify oneself with characters and situations – with the story – in a movie? Since we spectators are not actually there and then, we need to do it vicariously – and that happens when we, spectators, allow ourselves to become enmeshed in a given emotional, human situation; when we feel that it is us who are addressed by a character, in a dialogue – and we instinctively react to that, emotionally – and then compare our own reactions to that of the character addressed in the movie. In other words, it is through vicariously lived (“real” – that is, flowing, dynamic) human interactions that we are drawn in, into the given drama. And this is why it seems to me that this strange editing technique, by fragmenting and by making the characters’ interactions impersonal – also leaves us, to a good degree, emotionally outside – and contributes to the general feeling of “impersonality”. I guess that, for many, Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (

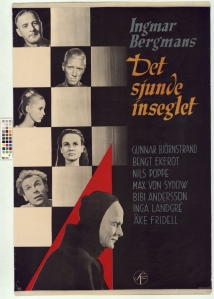

I guess that, for many, Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman ( I have seen Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (

I have seen Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal ( These being said (and we did just say a lot), let’s continue with our overview of the main characters of the film – and the next one in that review would be the character of Death itself, whose interaction with the knight Block (which begins at the very beginning of the movie) provides the framework and the interlude within which the entire action of the film takes place. (By the way, Block’s game of chess with Death, which starts at the beginning of the movie, and give the context for the movie, might just be a metaphor – for the movie, for the quest, and even for life itself… but, truly, enough with the metaphors!) Well, this “Death” fellow makes for a strange character. Not because it is “Death”; no, but because of the peculiar characteristics exhibited by this “character” in this work of art. For example, Death professes to be “unknowing” itself (!), and thus to not be able to say anything about the “after-life.” Well, normally, if “anyone” or anything should be able to say something about the after-life, that would be Death! So, what does this mean? Well, it seems that in this movie this character of Death is presented – and is seen – quite narrowly; that is, only through the perspective of what Bergman (and us, general humankind) knows for sure about “death”. And, what do we know for sure? well, mostly, we know it as a limit – universal, ineluctable, immutable, coming-for-everyone – but a limit is most or all that everybody knows for certain about Death. And therein lies the problem – that, if this is all that we, spectators, the general public, know about a character, it is not also what the character itself – what Death – would know about itself! In other words, it is strange the character of Death is presented through this, as it were, foreshortened perspective, being limited (as a character!) by our existing knowledge of it; when, in fact, Death should be the very character that would bring us new information – both about itself, and about what follows thereafter. (And this as well serve as the beginning of an explanation for why I was unsatisfied with the movie, and that dance macabre that concluded it.)

These being said (and we did just say a lot), let’s continue with our overview of the main characters of the film – and the next one in that review would be the character of Death itself, whose interaction with the knight Block (which begins at the very beginning of the movie) provides the framework and the interlude within which the entire action of the film takes place. (By the way, Block’s game of chess with Death, which starts at the beginning of the movie, and give the context for the movie, might just be a metaphor – for the movie, for the quest, and even for life itself… but, truly, enough with the metaphors!) Well, this “Death” fellow makes for a strange character. Not because it is “Death”; no, but because of the peculiar characteristics exhibited by this “character” in this work of art. For example, Death professes to be “unknowing” itself (!), and thus to not be able to say anything about the “after-life.” Well, normally, if “anyone” or anything should be able to say something about the after-life, that would be Death! So, what does this mean? Well, it seems that in this movie this character of Death is presented – and is seen – quite narrowly; that is, only through the perspective of what Bergman (and us, general humankind) knows for sure about “death”. And, what do we know for sure? well, mostly, we know it as a limit – universal, ineluctable, immutable, coming-for-everyone – but a limit is most or all that everybody knows for certain about Death. And therein lies the problem – that, if this is all that we, spectators, the general public, know about a character, it is not also what the character itself – what Death – would know about itself! In other words, it is strange the character of Death is presented through this, as it were, foreshortened perspective, being limited (as a character!) by our existing knowledge of it; when, in fact, Death should be the very character that would bring us new information – both about itself, and about what follows thereafter. (And this as well serve as the beginning of an explanation for why I was unsatisfied with the movie, and that dance macabre that concluded it.)

Together with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light, The Silence (

Together with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light, The Silence (