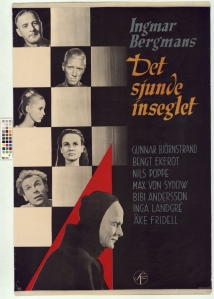

“dance macabre”

I have seen Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (synopsis; trailer; cast & crew: rating), a long time ago, so long that there was little that I remembered from it – before re-watching it very recently – besides a vague feeling of not having enjoyed it thoroughly, of having been somehow dissatisfied by it.

I have seen Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (synopsis; trailer; cast & crew: rating), a long time ago, so long that there was little that I remembered from it – before re-watching it very recently – besides a vague feeling of not having enjoyed it thoroughly, of having been somehow dissatisfied by it.

Well, after watching it again, I understand why it left me with those feelings. To put it very briefly (and somewhat vaguely), it has to do mostly with that dance macabre performed at the end of the movie, by most of the characters, under Death’s leadership… But let’s take things in order.

This film is somewhat different from others in Bergman’s body of work, being much richer in action (what happens “externally”) and number (and variety) of characters. I confess that I enjoyed these aspects of the movie (these “differences”) – as well as the fact that it is a kind of a “road movie,” which offers us a kaleidoscopic perspective of (a more-or-less imaginary, or real) Middle Ages. In other words, the movie possesses an “external” dynamism that is not present in some of the other Bergman movies (although all of them are rich in terms of the internal action, of what happens within the characters).

In terms of its “internal” action, then, The Seventh Seal seems to be engaged in the pursuit of some of the same questions that preoccupy Bergman in some of his other movies – and I am thinking here especially of his “God-trilogy”: Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, and The Silence (which were made within the seven year period that followed The Seventh Seal). This similarity in terms of the ”inner themes” is not happenstance, of course, as all these are auteur films, written and directed by Bergman himself. So, in a way, what we seem to have here is an enduring Bergmanian conversation or quest – in which we, too, can get involved, as viewers, or as fellow pursuers.

And what is this inquiry, this quest, about? I am not fond of treating works of art as “logical puzzles,” or of getting frantically engaged in looking for the meaning of metaphors, symbols and signifiers. I prefer instead that a work of art reveals what it has to reveal through (the portraying of) human existence itself – just as it happens in real life. (After all, in our “real” life we are not surrounded by walking symbolisms and metaphors.) That being said, when thinking about how to approach this movie, it occurred to me that one of the ways to do that would be by treating the main characters as, more or less, archetypes – in the sense of representing various ways of relating to life (and death), and of situating oneself within existence. Let’s go over these characters (and, presumably, archetypes), then, in order.

The main character – the hero of the story – is the knight Antonius Block. From the beginning we discover that Block is engaged in a struggle with the deepest questions, questions that he can not not ask – is there a God? why does He not answer? what is the aim of existence? – while also struggling with the fear of death (fear that spares none of the characters in the film). In this sense, Block seems to be the alter ego (or at least one of the alter egos) of Ingmar Bergman himself, as these are the very questions that drive this very movie, as well as those from his aforementioned “God trilogy.”

But, if this is one of Bergman’s alter egos, Block’s squire, Jöns, seems to be the other one – or another “side,” “facet,” or “face” of the auteur, of the questioner. (Perhaps, perhaps… needless to say, “perhaps”; as I do not have a definite explanatory key for this movie, nor am I fond of engaging in such quests for riddle-solving… but, let’s continue our exercise). Jöns represents (potentially) the “modern” person; that is, the modern “facet” of our questioner; that is, modernity, which has given up asking (the most important questions), because it has abandoned and reneged on the quest for God. As a result, the perspective that results from Jöns’ existential position is a cold and cynical one, a disabused one, of which the overarching characteristic is an ultimate lack of meaning. However, this does not stop Jöns from showing a degree of humane (humanistic?) compassion (toward the mute woman, or when Jof gets in trouble at the inn), as well as a sense of justice. But the overall impression that he leaves and creates is a disheartening one – and a slightly annoying one, as well, as when he keeps harping on the same dismal statements, and for which he is rightly shushed, at various times, by Block – and by Block’s wife.

But let’s get back to Antonius Block himself, the knight – who is probably the closest in spirit to the auteur / questioner himself, or at least to the question that is at the heart of the movie. Having returned from the crusades, after being gone for ten years – and after having witnessed, together with his squire, (presumably) much cruelty, misery, and meaningless suffering – Antonius is tortured by doubt; or, more accurately, by the conflict between his quest for knowing that God is, and God’s apparent silence in response to this quest.

(And, as mentioned, he doesn’t seem to be able to not ask, to can’t quell the need to know. “Do you never cease asking?” – asks Death (another character in the movie). “No, I never cease.” – replies Block. And why is that? Why can’t Block / Bergman stop asking? Well – says Block – because, “humiliatingly,” he can not “kill God” – or God’s imprint, or the need for God – within himself. And yet, this is a God that seems to remain silent, in the darkness into which Block keeps hurling his questions.)

So why does this God stay silent? In order to answer that, perhaps we have to look at the nature of the question that Block is asking. If we do that, we will see that what Block is actually looking for is not faith, but knowledge. And therein might just lie the problem – which, in many ways, is also (part of) our modern problem (or is it not?).

What do I mean by this? Well, it is known that Bergman was conversant with Søren Kierkegaard’s thought and works; and, indeed, I have seen glimpses of Kierkegaard in the ways in which Bergman approaches certain issues and questions, in other films (or so it seemed). But why is this relevant? Well, not for some “objective” purposes, such as examining whatever “influences” from Kierkegaard on Bergman, and so on. No, such things do not concern me, and should not concern us, really. The reason why Kierkegaard is of interest here is because he was engaged in a very similar quest, as Ingmar Bergman; at the height of modernity, he inquired into (and at) the intersection of faith, reason, and doubt.

If we employ then Kierkegaard’s perspective, and his results, it will become apparent that Block’s problem might be that the actual question that he is asking is not be the right one – inasmuch as what he is asking for is knowledge (certitude), and not faith. What is the difference? Why does this matter? Well, one of the important contributions brought by Kierkegaard to this issue was to clarify the distinction between the rational path of knowing, and faith’s path. Briefly put, for Kierkegaard faith is a specific kind of act or relationship, which begins exactly where reason’s powers end; that starts just beyond the limits of what reason can naturally attain to; in other words, that it is where the powers of reason falter, that faith, a qualitatively different act, comes about. After all, if “faith” and “reason” would have the exact same content, if they would be the exact same act, that there would be no need for different concepts to denote them.

Now, Kierkegaard was Protestant, which colored his approach, to a good degree; and this is why his explanation should (or could) be fleshed out with a bit of Catholic insight, as well – namely, that this distinction between the specific act of faith, and reason, does not mean that faith is an irrational act. No; it simply means that natural reason has its limits, and that a new path of knowledge exists as well that of faith – beyond reason’s natural limits. But why is then faith not irrational – if it goes where reason’s natural powers cannot carry us? Well, an answer to that is that, the universe being rational (intelligible), we also know that God (the Creator) is also rational (intelligible). In fact, this is why even pure, natural, unaided reason can and does take human beings, a good way, toward knowing God! However, there is a moment where reason’s “unaided” powers reach their limits; and this is where, while God remains the same intelligible, rational God, the path continues to be pursued, but through the aid of a qualitatively different act, namely faith. The Catholic tradition of thinking on the issue also adds to this that faith and reason, far from being contradictory, are in fact complementary – as two wings that help each other, and the human being, to know God. But, what does this all mean for the quest of our protagonist, Antonius Block?

Well, the quest in which Block/Bergman seem to be involved (consciously or unconsciously) seem to be that of inquiring about (the possibility of knowing) God within the modern context – a context defined (in many ways) by the fact that all other paths or means of knowledge – besides the empirical tools of Enlightenment rationality – seem to be excluded, to be unacceptable – not even talked about. It is in this exact context that the distinction between the specificity of the act of faith, versus that of the act of reason – as made by one of Bergman’s intellectual “partners of conversation”, Kierkegaard – becomes crucial. In other words, if you ask the wrong question, don’t be surprised if you do not receive the right answer; that a quest for knowledge, for empirical, provable certitude – and not for faith – will easily result in what looks like silence. Thus, if the characters in The Seventh Seal are archetypes representing various ways of relating to existence (that is: life, death, God), it would seem appropriate to add yet another character to this dance, one with whom Bergman was very much acquainted – that of Kierkegaard. And this character would be that of the “knight of faith” – who, by the way, is a crucial figure in Kierkegaard’s oeuvre – see the figure of Abraham in his book, “Fear and Trembling”. Introducing this Kierkegaardian character, then, helps us realize that Antonius Block is not a “knight of faith,” but a knight of doubt – and not of a doubt of faith, but a doubt that results from asking the incorrect question – which leads not to “knowing”, but to “silence”. (As Kierkegaard said – the opposite of existential doubt is not knowledge, but faith.)

These being said (and we did just say a lot), let’s continue with our overview of the main characters of the film – and the next one in that review would be the character of Death itself, whose interaction with the knight Block (which begins at the very beginning of the movie) provides the framework and the interlude within which the entire action of the film takes place. (By the way, Block’s game of chess with Death, which starts at the beginning of the movie, and give the context for the movie, might just be a metaphor – for the movie, for the quest, and even for life itself… but, truly, enough with the metaphors!) Well, this “Death” fellow makes for a strange character. Not because it is “Death”; no, but because of the peculiar characteristics exhibited by this “character” in this work of art. For example, Death professes to be “unknowing” itself (!), and thus to not be able to say anything about the “after-life.” Well, normally, if “anyone” or anything should be able to say something about the after-life, that would be Death! So, what does this mean? Well, it seems that in this movie this character of Death is presented – and is seen – quite narrowly; that is, only through the perspective of what Bergman (and us, general humankind) knows for sure about “death”. And, what do we know for sure? well, mostly, we know it as a limit – universal, ineluctable, immutable, coming-for-everyone – but a limit is most or all that everybody knows for certain about Death. And therein lies the problem – that, if this is all that we, spectators, the general public, know about a character, it is not also what the character itself – what Death – would know about itself! In other words, it is strange the character of Death is presented through this, as it were, foreshortened perspective, being limited (as a character!) by our existing knowledge of it; when, in fact, Death should be the very character that would bring us new information – both about itself, and about what follows thereafter. (And this as well serve as the beginning of an explanation for why I was unsatisfied with the movie, and that dance macabre that concluded it.)

These being said (and we did just say a lot), let’s continue with our overview of the main characters of the film – and the next one in that review would be the character of Death itself, whose interaction with the knight Block (which begins at the very beginning of the movie) provides the framework and the interlude within which the entire action of the film takes place. (By the way, Block’s game of chess with Death, which starts at the beginning of the movie, and give the context for the movie, might just be a metaphor – for the movie, for the quest, and even for life itself… but, truly, enough with the metaphors!) Well, this “Death” fellow makes for a strange character. Not because it is “Death”; no, but because of the peculiar characteristics exhibited by this “character” in this work of art. For example, Death professes to be “unknowing” itself (!), and thus to not be able to say anything about the “after-life.” Well, normally, if “anyone” or anything should be able to say something about the after-life, that would be Death! So, what does this mean? Well, it seems that in this movie this character of Death is presented – and is seen – quite narrowly; that is, only through the perspective of what Bergman (and us, general humankind) knows for sure about “death”. And, what do we know for sure? well, mostly, we know it as a limit – universal, ineluctable, immutable, coming-for-everyone – but a limit is most or all that everybody knows for certain about Death. And therein lies the problem – that, if this is all that we, spectators, the general public, know about a character, it is not also what the character itself – what Death – would know about itself! In other words, it is strange the character of Death is presented through this, as it were, foreshortened perspective, being limited (as a character!) by our existing knowledge of it; when, in fact, Death should be the very character that would bring us new information – both about itself, and about what follows thereafter. (And this as well serve as the beginning of an explanation for why I was unsatisfied with the movie, and that dance macabre that concluded it.)

I would say that this is some skewed and curiously “flat” character-building – which, I think, fails Bergman, as a creator, and fails the narrative, and fails us, the spectators. Why? Because each and every character that we encounter – just like any living human being that we would encounter in real life – needs to contribute (and naturally contributes) something that we did not know (because we are not them, because we only know them from the outside) to that encounter, to the narrative, and to our understanding (of them, of life, of everything). Such a closed, limited, flat vision of Death, as the one presented (apparently) in The Seventh Seal, has the opposite effect of limiting our understanding; thus this encounter, instead of enriching us, seems to strangely impoverish and limit – us, the movie, the quest. Quite frustrating and underwhelming, for me.

But let’s continue our discussion of the main characters / archetypes.

The next archetype is represented, perhaps, by what the French would call saltimbanques – travelling performers, artists, jesters; more precisely, a family of artists composed of Jof (Joseph), Mia (his wife), and their small boy, Mikael. What do these artists represent? Perhaps – innocence, simplicity; simple and natural life; the simple pleasures and benefits of everyday existence. Tellingly, they are the characters to whom Antonius Block relates the most favorably, in the movie, and in whose company he seems to be in the “sunniest” disposition. As he asks Death for additional time, to do “one more meaningful thing,” it will be this family of artists who will actually benefit from that act – as Block will (apparently) save their lives by detaining and derailing Death’s attention from them. In a way, this family of artists represents a counterpoint to the Block/Jöns duo – who are grim, heavy and laden with the memories and deeds of war (sinful?), versus the members of this family, who seem light, hopeful, and wholesome, and perhaps naturally innocent (and I find that a bit problematic, but more on this later).

Other characters – archetypes – are: the bad clown (or artist, or saltimbanque – who is, somewhat deservedly and appropriately, taken by Death before all the rest); the violent, impulsive, yet somehow likable blacksmith, and his prodigal wife (who has an affair with the “bad” artist); the mute woman (a woman who follows Jöns, after being saved by him from rape – but probably follows him simply out of a lack of alternatives, and basically for safety); and the fallen priest (or seminarian, who seems to have been the instigator of Block’s initial departure on the crusade, but who is now a lost soul, selfishly preying on both the dead and the living, and ‘preaching’ through his actions and demeanor a message of despair and cosmic abandonment); and, finally, Block’s wife, whom we meet only the end, when she welcomes Antonius and his travel companions at the manor, yet whose presence and actions make her a distinct voice in the entire narrative.

These being the main characters, let me also mention some moments from the film that I found interesting, revealing, or telling (for fleshing out the story, the quest, or the characters; or, just interesting). For example, how the mute (lost) woman suddenly speaks (!), but only at the very end, when she sees Death; and her transfigured face even seems to express a sort of happiness, or maybe relief, as if of finally being relieved from a tortured existence; her last words, tellingly, are “It is finished” (hearkening – not sure why – to Christ’s final words on the cross).

Then there is the fact that the ex-priest (who is now a ravenous wolf, and whose life is now a message of egotism, hatred and despair; and who is probably the most negative character in the entire movie) dies of the plague, in great suffering. uncomforted, and left utterly alone – although all of this happens within the eyesight (and in the context of the non-intervention) of teh entire travelling company (Antonius Block, Jöns, the mute woman, the blacksmith and his wife, and the family of artists). It seems therefore that his death matches his cosmically alone and desperate existence; that his abandonment of every other human being, during his lifetime, is matched by how he is abandoned by everyone else, when he dies (“Is there nobody to comfort me?”, he cries; no, there is none.).

There are also several scenes involving a young woman – mentally or spiritually deranged – who is accused of witchcraft or demonic possession (and who also accuses herself of the same); and who is taken to be burned; but whose sufferings are (humanely) shortened by the ingestion of some substance fed to her by Antonius Block.

Somewhere around the middle of the movie there is also a scene in which two “spectacles” are being juxtaposed – one, of the saltimbanques putting on a humorous play of some sort, to informatively entertain the peasants during these times of plague (and the village folk are entertained, to a degree, but overall are only half-attentive) – and the other, of the entrance of a wailing, grim cortege of penitents (who do attract the frightened and impressed attention of all the people). So, what do these two parallel spectacles represent? Two responses to the plague? Or, two types of existential responses to “plague” of death, itself? Or, a commentary on the people’s own ways of dealing with these heavy issues – that they are generally inattentive and scatterbrained, and only receptive to being frightened?

Speaking of the “people”, it is interesting how the “general” public (or at least the wide cross-section of people that is present, eating and drinking, at the inn) is portrayed as being characterized mostly by ignorance and by ill-will. In other words – the “crowd,” the mases, are not “good;” and they do not represent a “solution” (a message with which Kierkegaard would resonate).

But, why the plague? Why does the plague (that is ravaging the country) give the overall context and background for the movie? Could it be that its (threatening, unseen) presence gives Bergman (and the movie) the context and opportunity to ask questions that would otherwise (and usually) be avoided (especially in our modern context)? In fact, the plague – which can take anyone, anytime; which hangs, threateningly, above and around everyone – seems to be similar, in many ways, to death itself (which also hangs, unseen… etc.). And, while the plague might not be around, today, death still is – and yet, the fundamental questions about death (and existence) are no longer posed, in our (and Bergman’s) modernity. The very setting of the story in (Bergman’s vision of) the Middle Ages might serve a similar purpose, as well: to allow him (and us) to ask such questions, questions that in modernity are simply muted (yet which are no less “actual,” important, and universal, as in any other moment of human history).

But perhaps now would be the time – after this overview of characters and situations – to tackle that “unsatisfactory” ending, and why I found the movie, overall, slightly disappointing. Yes, I did find the movie engaging in numerous ways –through the richness of its action and of its characters, as well as through its road movie-like survey of a more-or-less imaginary “Middle Ages”. All that was enjoyable – and I found that satisfactory. The “quest,” however, which drives the movie, was not as satisfactory, in the end – and I mention this because that is not the case with what happens (with the same quest) in his “God-trilogy” of Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, and The Silence. And what is the major difference between this movie, and the pones from that trilogy? Well, perhaps it is the fact that in those other movies the principal quest – and thus our questioning – remain open (as it is appropriate, in a work of art)

Can those movies be interpreted in different keys, some that might be similar to the “answer” given by The Seventh Seal. Yes, why not. However, ultimately those three movies do not close the question, but leave it open – by leaving the interpretation of the movie open to us, those who encounter and engage with the work of art. But why do I say that The Seventh Seal does it differently – and wrongly; and what is my problem with that “dance of the dead” (dance macabre) that concludes the movie? Well, it all has to do with that flat or foreshortened perspective on Death that we discussed above. When, at the end of the movie, all (or most) of our main characters are chained in a long, grim and wild dance macabre, being led by Death (with scythe and hourglass in its hands) toward (it seems) the “dark territories” – then Death, who is “unknowing” in this film, has the last word – and that is not right. And the problem is not that Death has the last word – but that this ignorant Death, this flat character that has brought little or nothing to the dialogue, does that. In other words – we start from ignorance, we meet a Death character that is flattened and impoverished by having been designed by Bergman according to said initial ignorance (so why introduce it, then?), and we end with the same. Most unsatisfactory.

Unsatisfactory, because this also closes the meaning and reach of the film, as a work of art. A work of art’s goal and mission is to engage the person who encounters it; art happens at and in this meeting point – that is what art is. No matter the artist’s own interpretation, or position, the true artistic object – once produced – obtains a life and being of its own, imbued with meaning, which comes alive in and through the interaction with each separate, individual person (each of them bringing their own world of understanding, experience, meanings – to this encounter). This is what it means for a work of art to be alive – it is and comes alive, in this encounter; in each encounter, anew, as long as it will exist. But, for this encounter to happen, the engagement needs to be left open, possible, un-closed. (This is why propaganda or ideology results in dead art,) Bergman most certainly did not engage in any such closed-thinking attempts, such as propaganda. However, comparing The Seventh Seal with the God-trilogy, I feel that (no matter Bergman’s own verdict) at the end of each of those other movies I am left still open, free, and thus continuing to engage and converse with the artistic object – long after having seen it. While many aspects of this movie do keep me engaged, hours and days after seeing it, I feel that it is exactly in its main quest (or what I think is its main quest) that it fails to do so – because the movie seems to close the very quest in a flat, unsatisfactory, and disappointing manner. Or so it seems to me.

Because, of course, other interpretations (even of that ending) are also possible (of course!). For example, let’s take the family of traveling artists. One thing that we do know, from the movie, is that they are the most positive characters in it – as said, somewhat in juxtaposition with the disheartened & disillusioned Block/Jöns duo. However, if this is, as it were, Bergman’s positive answer to “the quest” – if this is it, the great answer, as it were – well, then the “answer” is both underwhelming and problematic. Yes, there is something – in fact, quite a lot – quite attractive about the wholesome, simple, (even) naturally innocent picture of this family; on the other hand, if this is the solution, Bergman’s answer, this idealization of “natural life,” of the “natural pleasures of life” – then it is, how shall I put it, quite simplistic, low brow, underwhelming, and unworthy of Bergman’s artistry. Furthermore, if this is what they are meant to represent, then, although this movie was made in 1957, this seems like a foreshadowing of the hippie era of the 60s and 70s; and, let’s be serious, we all know that they were quite far from being the “answer” to anything.

But there is yet another possible interpretation (and, I’m sure, many others). Somewhere at the beginning of the movie, and somewhat passingly, another aspect is introduced – which is not repeated or insisted upon, later. Namely, right at the beginning there is a scene of Jof having a most luminous, light and peaceful vision of the Virgin Mary (as a queen) walking her unclothed baby boy, Jesus (through the grass). And we are told that this is not the only vision that he’s had (of such kind)! So, what does this mean? Does this artist family represent (and contribute thus to the movie) an “open”, luminous possibility – that same open, luminous possibility that seemed to have been closed by the grim dance macabre at the end? Furthermore, the simple and direct way of “seeing” of these people (the artists), might it even be a metaphor for faith (?) – as different from Block’s quest for sure knowledge?

Or, perhaps, are the characters chained to and dancing behind Death, the “sinners” (because, yes, most of them are burdened by concrete sins, that we know of), being taken (as Jof says, when he sees the dance macabre in his vision) toward the dark territory? While, au contraire, are the members of the family of artists… the innocents (in this story)? But then, given that Antonius Block did actually perform a very meaningful (and good!) final deed, saving this family of artists, why is he also in that dark chain of death? Yes, I don’t know…

But, as said, I am definitely not fond of trying to solve “riddles” – so I will let all this here be as it is (was). Was this an enjoyable and engaging, even entertaining movie experience? Yes, it was, in many ways. At the end, however, it turns out that my vague memory proved to have been correct, and that things have not changed – that this movie, as an artistic and existential experience, does still leave me somewhat unsatisfied, slightly disappointed – for the “dance macabre” reasons explained above.