“beautiful, but somewhat impersonal”

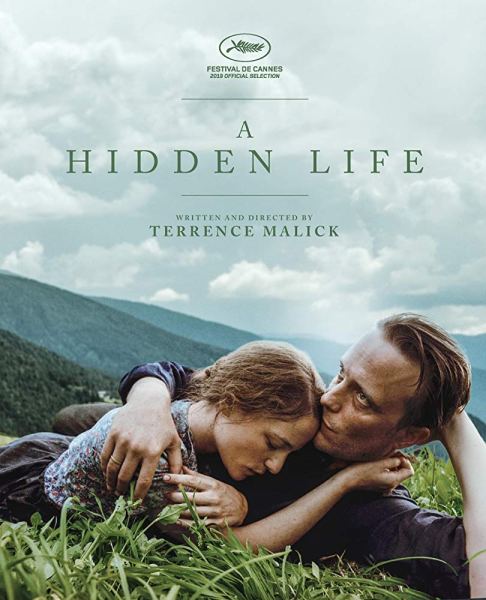

Soon after beginning Terrence Malick’s newest film, A Hidden Life (synopsis; trailer; cast & crew; rating), one is reminded of the style of another film of his, The Thin Red Line; more precisely, in the tone and in the approach to telling the brief story of how Franz met Fani – which is very much like the dream-like remembrances of Jim Caviezel’s soldier in The Thin Red Line, about his desertion and his time among the islanders.

Soon after beginning Terrence Malick’s newest film, A Hidden Life (synopsis; trailer; cast & crew; rating), one is reminded of the style of another film of his, The Thin Red Line; more precisely, in the tone and in the approach to telling the brief story of how Franz met Fani – which is very much like the dream-like remembrances of Jim Caviezel’s soldier in The Thin Red Line, about his desertion and his time among the islanders.

And perhaps it was during the filming of that movie, The Thin Red Line, that Sean Penn got very irritated when, one day, when Terrence Malick was supposed to film one of Penn’s scenes, the director’s attention was attracted instead to a feature of nature (a butterfly? a flower?) – and he turned the camera in that direction, and away from Penn – which, of course, the prosaic, earth-bound and very literal Sean Penn found to be utterly pointless and incomprehensible. I must say that I am on Terrence Malick’s side, on this issue, in general – as Malick’s is a contemplative gaze, to which I can very much relate; however…

However, the tagline that I chose for this discussion, “beautiful, but somewhat impersonal” (which could also have been “beautiful, but somehow unaffecting”), points to what seems for me to be, in this movie, an imbalance between, let’s say, the lyrical and nature-oriented gaze of Malick (to which, again, I can relate) – and the need to tell a compelling human story (which requires the establishment of a human connection between us, spectators, and the characters – and their story).

Because this is, indeed, an important story – not in some objective, abstract, socio-political way, which I would find quite unappealing – but in the sense that it talks, essentially, about the dignity and the sanctity of the individual conscience, and about the noble (yet deeply personal) acts that result from acting according to one’s conscience, while faced with, and over and against, the dirty and cold waves of history. In other words, it is a story that talks about some essential truths of the human condition, through a very personal story – which means that it would have to immerse and to involve us deeply, intimately, personally, with this “hidden” story (and I think that that was Malick’s intent, as well); and yet, in this case the movie remains, ultimately, “somewhat unaffecting”, “somewhat impersonal”. And one wonders why that is so…

Well, in order to attempt some answers, let us get back to that “gaze at (or on) nature”. There is a lot of beauty, in fact a tremendous amount of beauty, in this movie; and a lot of it comes from the astonishing (yet most real) scenery in which the story is set (in the movie, and in the real life) – the scenery of the Austrian Alps. Every mundane moment is thus inundated with this “impersonal” beauty of the natural surroundings – even the daily moments on the farm, which are spent in domestic, everyday activity etc.

However, at the end of the day natural beauty (as beautiful as it is) can only be – and always remains – “impersonal”. And yes, there is something to be said exactly about the juxtaposition of this natural beauty, and the ugly, hard things happening in the world of men, in the same context – and Malick is well aware of this tension. Yes, he seems aware of the fact that nature always remains “neutral”, an un-contributing spectator, a canvas upon which us men can paint – well, anything, good or ill; and of the fact that nature, even in its most stupendously beautiful instantiations, cannot represent a true “escape” from it all, from the human condition. In fact, the entire movie starts with one of the main protagonists relating how they had hoped, initially, to escape the ugliness “of the times”, of history itself, in this remote beauty and in the familial coziness that they had constructed for themselves, on the farm, in their small village – but in the end it turned out that that is impossible. Because the ugliness does not come in fact from “somewhere else”, from some outward “society” – but from the hearts of men, wherever they may be, even in the most beautiful surroundings; and some of the people from the village “community” (which, initially and superficially, seemed so idyllic) will soon reveal the evil (or cowardice, or simply moral mediocrity) that lives in the hearts of men. And – as another quote from the movie puts it – “Nature does not notice the sorrow that has come over the people” – nature does remain, in the end, neutral, impersonal.

Yes, Terrence Malick, the writer-director, is aware of the fact that nature is no beneficent god, either – although, seem to hint Malick, it is the creation of beneficent God – and, in its stupendous beauty, perhaps a prefiguring of how things should be, or of how they will be, when the world will be “made anew”. Thus, at the end of the movie, the wife, Fani, pictures them – her, Franz, and the children – meeting again in an afterlife that is a “world remade”, according to how God seemingly actually wanted it. But! – but here, now – nature remains neutral.

And so, if Malick is aware of all this, what is then the problem (or is there one?) with his “gaze on nature”? And does this problem, if there is one, partially also explain why the movie remains, as I said, ultimately (somehow) “unaffecting”? Without pretending to know better than Malick how he should do his job, I would nonetheless remark on this issue that the entire movie feels as if the story is reflected off the natural surroundings, somehow indirectly – and thus that there is a certain feeling of impersonality about it all. But why? Doesn’t Malick use – which I found quite attractive and instructive – a very low, oblique, close camera angle, when filming the protagonists? – which is brilliant, as it gives the camera (and us) a certain degree of intimacy, by entering, as it were, into the private, individual sphere of character? Isn’t this actually meant to get us close to their personal, “hidden” story? So, why don’t we get thoroughly involved, then; why don’t we become then deeply involved, with each of them, and with their story?

Let’s get back to nature, and to the fact that the story seems to be, as it were, “reflected” off the mountainside. What do I mean by this? Well, I guess that by this I am referring, perhaps, to an over-abundance of natural sights that – and I think that this is the important part – never becomes parts of the story. In other words, that there is a kind of lyricism (even natural lyricism) that “goes along with the story”, that uses the surroundings to tell the selfsame story – and there is also a lyricism that works, seemingly, in disjunction with the story, and that remains thus somewhat cold, apart; and the latter, I think, is what is happening in this movie. (I should perhaps repeat here that I am fully on the side of lyricism, as such – even natural lyricism.)

Yes, this could be one of the contributing factors – or an occasion – for that distance that seems to exist, throughout, between us and this story – and the intimate life of these characters.

Moving on, another reason for that partially “unaffecting” quality might be the fact that there is a kind of a static nature to the story-telling, in this movie – that the narrative feels somehow static. Oh, make no mistake! – the “historical” (contextual) narrative does progress, as indicated by the various time stamps (announcing the given month and year) – and as illustrated, in several instances, by some aptly used historical footage (black-and-white silent reels that are wonderfully used to create a sense of the political and historical context; so well done, in those small capsules, that for me this really represents a model for how to do such things). But the story that remains static is the story of our characters – which is the most important one.

And, again, here I am not referring to their external story – after all, once Franz gets imprisoned, while his family continues its seasonal life on the farm, there is little that would in fact be happening – visibly, externally. But the true story – and the one that Malick actually wants to narrate, I think – is the inner, “hidden” story; and yet, the way the movie’s narrative is shaped and cut, not much – or not enough – is transmitted to us about what happens there, within: in the conscience, where the most important things happen.

Yet in reality – and in Franz Jägerstatter’s case, for sure – things are always happening, there, within; it is never quiet, boringly quiet, in our soul! So the static nature of the narrative, that I am complaining about, refers to the inward story – that it is to that tumultuous inner story of Franz (and of Fani etc.) that we should have been made privy – in order for us to become really, truly, deeply involved – that is, emotionally, personally, existentially involved. But is this inner story absolutely never shown, in its power and intensity? Oh, no, some two-thirds into the movie there is a brief period when suddenly (or so it seemed to me) we become introduced, immersed into the intense and troubled ocean of Franz’s inner, spiritual life; and that period of the narrative is, accordingly, gripping. But then it lets off… Yet this, this sort of drawing of the viewer into the inner life of the protagonist, of actually presenting the ever-changing, tumultuous waves of their (of Franz’s) interior life, should have been the main narrative “hook” (or device) of the movie – which would have kept us involved and, well, “hooked” into the most important and the most dramatic story, of the “hidden life” mentioned in the title. But this inner, hidden life is only partially – only at times – or only indirectly – presented, in the movie.

And yet, I think that Malick’s intent was in fact to draw us in and to present it, this hidden life, continuously and throughout the movie – hence all the monologues, and the personal, contemplative moments; and yet we remain mostly outside of them. Why?

Well, perhaps there is another reason, as well. (And let me say it again – “not that I assume to know better than Terrence Malick what he should do”; in this regard, see also our general disclaimer.) However, another reason or cause for this “somewhat un-engaging” quality of the movie might have to do with the fact that the dialogues (by which I mean an uninterrupted, flowing, back-and-forth, emotional, physical and verbal interchange, of action-and-reaction) are never really allowed to take place, to be present in this movie. Instead, they are cut (edited) in such a way, that what result are fragments, parts of interactions; in which a character utters something – then there’s a cut – then another character utters something – and so on; and what results is almost like aphoristic statements, bypassing each other, or directed at each other, but never becoming a part of an organic interchange, an interchange of which we ourselves can become a part. And this, indeed, is an important problem – that this movie-making technique never really allows us to become truly involved – that is, to project and to immerse ourselves into the interchange between the characters, and thus into emotional situation, and thus into the characters themselves.

Because, how does one get to identify oneself with characters and situations – with the story – in a movie? Since we spectators are not actually there and then, we need to do it vicariously – and that happens when we, spectators, allow ourselves to become enmeshed in a given emotional, human situation; when we feel that it is us who are addressed by a character, in a dialogue – and we instinctively react to that, emotionally – and then compare our own reactions to that of the character addressed in the movie. In other words, it is through vicariously lived (“real” – that is, flowing, dynamic) human interactions that we are drawn in, into the given drama. And this is why it seems to me that this strange editing technique, by fragmenting and by making the characters’ interactions impersonal – also leaves us, to a good degree, emotionally outside – and contributes to the general feeling of “impersonality”.

Because, how does one get to identify oneself with characters and situations – with the story – in a movie? Since we spectators are not actually there and then, we need to do it vicariously – and that happens when we, spectators, allow ourselves to become enmeshed in a given emotional, human situation; when we feel that it is us who are addressed by a character, in a dialogue – and we instinctively react to that, emotionally – and then compare our own reactions to that of the character addressed in the movie. In other words, it is through vicariously lived (“real” – that is, flowing, dynamic) human interactions that we are drawn in, into the given drama. And this is why it seems to me that this strange editing technique, by fragmenting and by making the characters’ interactions impersonal – also leaves us, to a good degree, emotionally outside – and contributes to the general feeling of “impersonality”.

But I guess (and it is just a guess) that Malick might be counting on us to simply, as it were, jump into the given emotional moment; to empathize punctually with specific moments, feelings, states of the characters – but how in the world could we do that? To give an example of what I mean – at various points in the movie, different characters, seen on their own, burst into tears, their face is distorted by suffering (e.g. the mother) – but they’re suffering about what? Of course, intellectually we know what it is all about – but we have not been led, emotionally, into this inner suffering, through the mediation of living relationships. And thus we just watch these scenes – and we remain, as said, somewhat remote, somehow uninvolved.

These might be some of the reasons why – or ways in which – this movie does not become as engaging as it should be – and, I think, as it actually wants to be. And yet the story is supposed to be – and is, essentially, fundamentally – about the most personal, “hidden life”, of the individual; about the inner drama of the soul, of the conscience, opposing the larger, much too large, waves of politics and of history. In other words, A Hidden Life is not only a poignant story about the violent and brutal twentieth century (which had Nazism, fascism, communism) – but talks to the deepest truth of the general human condition – while also being based on a real, true story, of Austrian peasant Franz Jägerstätter.

And Terrence Malick shows us in fact that he understands many aspects of this inner drama; and he demonstrates exquisite existential sensitivity and maturity, when depicting various subtle aspects of this drama. See, for example, his depiction of the barrage of attacks (a relentless avalanche thereof) directed at the moral position taken by Franz, by his conscience (and one is so frail! and so alone!) – attacks that come from literally everywhere: from people official or unknown, to fellow villagers, to the people closest to oneself, and to those who in fact should help guide you in these inner travails. And often these “attacks” are in fact motivated by the best intentions – or so they think (as often they come from sheer human limitations). Think, for example, of one of the most hurtful yet well-intentioned “attacks” – of his mother reminding Franz about how his father, too, died in a war (World War I), and thus how Franz knows what it means to grow up without a father; and that she, the mother, knows also what it means to remain a widow… And how can Franz not be torn to shreds, inwardly, by this – thinking about his own wife, and about their three little daughters, all of whom he adores!

Or, the even more insidious and undermining “attacks”, about which you don’t actually know whether they are in fact “attacks”, or whether it is but reason (finally) speaking sense to you! For example, the inner and outer questions which Franz must answer, like: “is this not your pride?”; “who do you think you are?”; “do you think that your gesture will change anything on a grander scale, in the world?” (“no, but it makes a world of a difference for my soul”); “is refusing to say the oath to Hitler, which are just some words, which nobody believes anyhow, and which you can deny while saying them – is this worth the suffering that you will incur on yourself, on your wife and family, and perhaps on your friends?” – and so on. Or, the worst of all – the inner doubts that one has to face about the very morality or spiritual rightness of what one is thinking or feeling – inner doubts that question the very foundation of the moral position that you are taking, on those very same moral and spiritual grounds… ah, what amount and variety of suffering!

And see Malick’s depiction of the conclusion – or decision, rather – reached by Franz Jägerstätter, a decision reached by many of his fellow-sufferers, who lived in similar prisons under other totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century; namely, that when you find yourself in a situation with no real hope of future escape or release, yet under constant duress and threat directed at your “future” life – that the ultimate solution and escape, which takes out the sting definitively from all their threats at your life and at your future, and that will paradoxically make you free – is to “give up on the idea of surviving at any price”; to admit that you are already, effectively, dead, renouncing all hopes for a future life “outside” – and then, as Franz says, “a new light floods in”. In other words, that the solution is not to give up your life, per se, but to give up on the world, on the hope of escaping and of enjoying life in the future, in the world – which will free you existentially, which will make you completely free (as Franz says, to one of his captors: “But I am free [already]!”) – because thereafter there is nothing that they can do to you, that they can threaten you with, that they can truly take away from you, anymore. Because the only thing that they have, the oppressors – are physical, external, temporal, worldly threats – of taking away your “outside” world, your “outward” future, your “temporal” life. But, if and when you give up on that hope of ever escaping, of getting out, of returning to the world – you can become spiritually (and utterly) free. (And this in fact is also the perennial experience and discipline of the monastic communities. whose members make a conscious and willed choice of renunciation, of “dying to”, the world – in order to become truly free, in their souls – and to belong only to God.)

What a tremendous statement, this, about the superiority of the spirit, of the human self – even against the most brutal dictatorial regimes! And what a great thing that Malick is aware of all this, of all these obstacles and trials – I guess, through readings, meditation, through thinking about the issue – and, I would say, through pure artistic and human sensitivity!

And it is also refreshing to see – and something to be appreciated – that Malick seems to understand genuine, adult faith – and is able to depict it, in its noble simplicity. This is, indeed, quite a rare feat, nowadays (or always?). Indeed, the drama of “the hidden life”, that this movie is about, and that represents the central conflict of this story, is actually a spiritual drama. Thus, being able to understand faith, and the life of the spirit – and the tradition of thinking about these issues, and of the lived experience of faith – represent necessary skills and attributes, if one is to depict such a “hidden” story; and my appreciation goes to Malick, for possessing such intellectual and existential knowledge – and sophistication (or, perhaps, simplicity).

But, speaking of the conflict between the individual and the world, let me open a larger (yet focused) parenthesis, to note something which I do not think is the result of happenstance, of accident. I am referring to Terrence Malick using, in fact almost quoting, idea for idea, from the writings of Søren Kierkegaard. This is perhaps most evident (although there are several, even many such occasions) in the scene in which Franz converses with the artist painting the church ceiling, in which the painter talks about the relationship between art / the artist and the great dramas of existence – and, more specifically, the life of Christ that he is depicting (which is the central drama of human existence, for a believer). For example, during this conversation the icon painter asks himself how do artists dare, in fact, to depict such things – which were real! which have happened in reality! (for example, the sufferings of Christ); in other words, how can an artist approach this real suffering, simply aesthetically, and thus putting a certain distance between himself and the reality and truth of what he depicts – and, moreover, even earning a living, making money, out of doing this? Is there not a deep, and at the end of the day thoroughly disheartening, contradiction, in all this? – on the one hand, the reality of the drama and of the suffering – and, on the other hand, the comfort and the distance of the depicting artist? This is related, as well, to the difference between being an admirer or being an imitator (a “follower”) of Christ – says the painter; between one who looks at what Christ did, admiringly, but remaining uninvolved, remote – and one who starts living out His example. For example – says the painter – the majority of the people in the pews will look at what he just painted (e.g. scenes from the life of Christ) and will see them as, well, things that happened a long time ago, centuries, maybe millennia ago; and this will allow the people in the pews to say to themselves that, surely, they would have never done what those evil people did to Christ, back then, a long time ago! Yet… what do the villagers do in relation to Franz, in their contemporaneity? In other words, both the people in the pews, and the painter himself, are in fact putting an existential distance between themselves and what is depicted, that sacrifice, that moral drama – when, in fact, what they should be doing is to put themselves in the situation, to approach the story as contemporaries of what is depicted – involving themselves personally and intimately, and asking themselves the hard existential and moral questions of – what do I do, what should I do, today? Because, in fact, the moral and existential challenge, and drama, and provocation – the same choice between truth and lie, good and evil, that crucified Christ – is facing me now, today, and everyday! And, when we are watching this dialogue between Franz and the painter, and the movie A Hidden Life, and the moral conflict depicted – aren’t we the people in the pew, and isn’t Malick the painter in the church?

Well, all this conversation, all these musings, are in fact Kierkegaard’s reflections on the topic as developed in one of the essays of the volume, Practice in Christianity (the essay titled “From on High He Will Draw All to Himself”). Of course, the choice of Kierkegaard is very apropos and apt, given the central theme of the movie; as Kierkegaard’s thought and works was dedicated, to a good degree – and especially toward the end of his life – exactly to the conflict between the individual’s conscience, versus the crowd, the outward world, the ephemeral pressures of one’s time. So, a movie dedicated to this conflict – and a movie that wants to point out the utmost importance of the hidden story of the soul, over and against the vagaries of worldly existence – would do very well to be nourished and informed by Kierkegaard’s thought! (And I will mention just one other such Kierkegaardian moment from the movie, also because it is very telling; namely, when Franz asks himself, “does a man have the right to allow himself to be put to death for the truth?” – which is basically the very title – and, of course, the theme – of one of Kierkegaard’s essays from the the cycle titled, Two Ethical-Religious Essays.)

But, you might ask, is Malick’s usage of – his quoting, paraphrasing of – Kierkegaard so important, that it had to be included in this discussion about the movie? Overall, maybe not – but I just found it so delightful and surprising, that I wanted to discuss it, briefly; while, on the other hand, also pointing the interested reader of this discussion to “further readings” on the topic. And let me just conclude this parenthesis by wondering very briefly about how Malick actually arrived to Kierkegaard (a wondering with no evidentiary background, as I prefer not to read interviews with the auteur, before discussing the movie). I wonder in this sense whether Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s writings (the German Protestant theologian whose fate in Nazi Germany was very similar to Franz Jägerstätter’s – and who also meditated and wrote a lot on the topic) might have been a textual source for Malick – and thereafter a conduit to Kierkegaard himself. In any case, let us close this (by now, long) parenthesis – which I enjoyed, but I don’t know about you – here.

A few other details or aspects of the movie, that I find worth mentioning, would include, for example, the superb, sensitive and millimetric performance from August Diehl (as Franz Jägerstatter) – frail, but strong-wired; thin, but like a rock, inside; ascetic but of childlike simplicity; stubborn, but with humility – a wonderful, thoroughly wonderful performance!

I would also point out the excellent choice of using Austrian and German actors – who therefore speak English with an accent – which contributes to making the story both unostentatiously authentic, as well as approachable for the world audience. And, associated with that, the wise choice of leaving some of the contextual or background dialogue in Austrian (German), without adding subtitles; indeed, these words did not need translation, because we understood their gist (the attitude, the context they depicted) – which was a choice that further contributed to our immersion into the given time and place.

I would also remark, with delight. on Malick’s choice of giving significant attention to, and of also presenting the travails and struggles of, Franz’s wife, Fani – in parallel and accompanying, as it were – from a (long) distance – her husband’s own prison sufferings; and illustrating how they both had to carry the burden and the consequences of the choice – just like the choice itself had to be talked out, negotiated, wrangled about, and probably made, together, by the couple. (The movie was thus a delightful picture of marital love, as well.) It is rare when an author understands and presents, with such an attentive eye, and without off-putting ideological biases, the reality, specificity and uniqueness of the woman’s strength, even heroism (instead of either ignoring her part, or of depicting her as a man – both of which miss the specificity). Another movie in which I saw this done very well, in fact even better, was Apocalypto – in which the thrilling adventures of the husband’s (endless) jungle chase are accompanied and paralleled, far away, by the astonishing and gripping drama of the wife’s fight for survival, for defending herself, her children, and a baby who is just being born – all of this happening within the narrow, oppressive, and frightening confines of a hole in the ground; truly striking! But it takes an eye that is both artistically as well as humanly perceptive, and intelligent, to be able to depict this, the woman’s unique drama, and her matching strength – like these two movies do.

And – while much more could still be added, about A Hidden Life – I will only add one more small detail to this discussion, namely the immensely enjoyable and funny moment when Franz responds to the villagers’ salute of “Heil Hitler!”, with a completely unexpected (and thus even more delightful) “Pfui, Hitler!” (phonetically, “Phooey, Hitler!”)! So funny, endearing – and so expressive, in fact, of Franz’s persona – in which both child-like simplicity, and moral courage and maturity, combine, coexist, and are expressed!

To conclude, A Hidden Life is a beautiful, noble and ambitious movie that draws our attention to the inner drama which is, in fact, the real and most important drama of the human existence – a drama depicted through the (real) story of Franz Jägerstätter, a man of conscience and of faith, who anonymously and unexpectedly stood up to the overwhelming pressures of his own times. Given the intent and depth of meaning of this story, it is that more unfortunate that (for a variety of reasons) the movie itself ended up being both beautiful and noble, but also somewhat impersonal, partially unaffecting – ultimately not managing to truly and definitively draw us in, personally and emotionally, into the heart of this inner story.

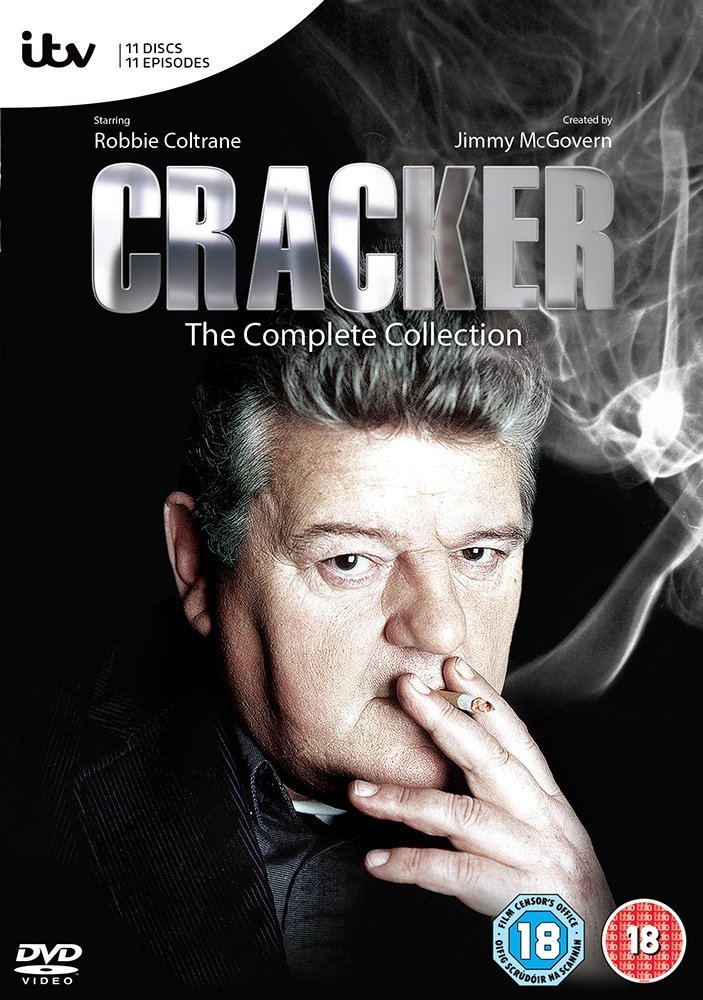

The two main things that contribute to making the TV series

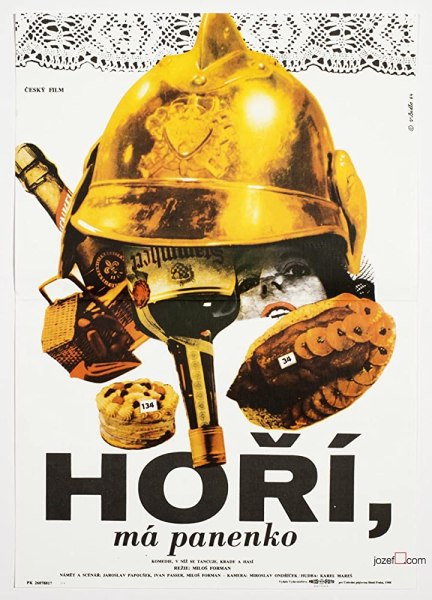

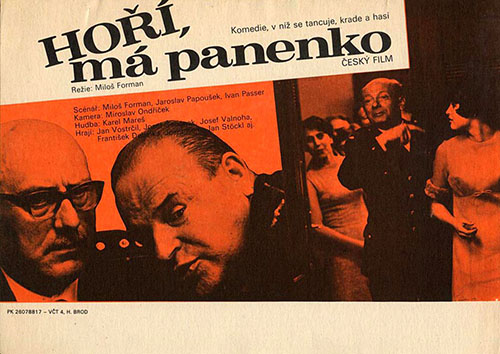

The two main things that contribute to making the TV series  Miloš Forman’s The Firemen’s Ball (

Miloš Forman’s The Firemen’s Ball ( Without going into too much detail about the specific ways in which the movie achieves this type of communication (because that would spoil the fun), I will however point out some aspects, or moments, just for the sake of clarification, and to be able to discuss the “satire” dimension of the movie. Take, for example, the “fire brigade” – which works as a perfect metaphor for the “Communist Party”; starting from the casting, with the “president” of the brigade looking exactly like a Party Leader from any Central or Eastern European Communist country; to the very modus operandi of said brigade: secretive, behind closed doors, and more concerned with appearances, than with true achievements; referring to “the people” as a “them”. vs ”us”; and always making sure, without daring to admit it, that they collect the material spoils; but being keen on maintaining the appearances, for example by organizing a ball “for the people”, and also an “official ceremony” for a “respected” (but in fact ignored and neglected) former “president” of the brigade; and clumsy and incompetent and haphazard in all that they actually do, as it always happens, in such party-states; and abusive and exploitative toward the public, in fact, as evidenced by how they “recruit” (or, rather, “snatch”) the girls for the beauty pageant etc.

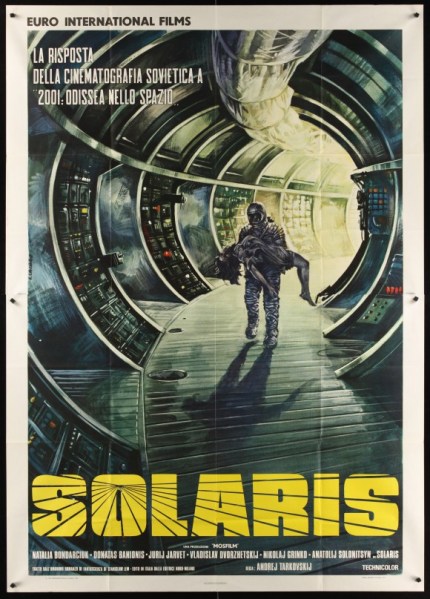

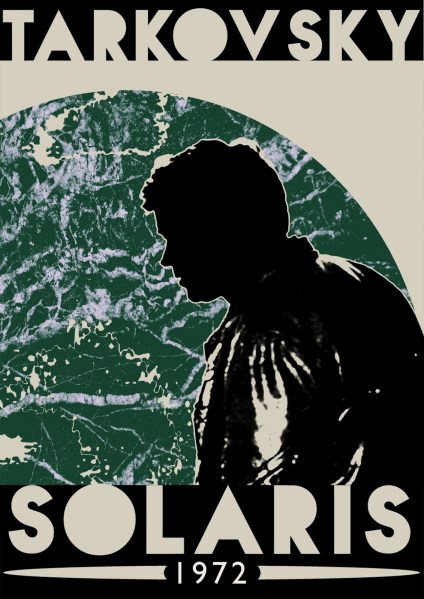

Without going into too much detail about the specific ways in which the movie achieves this type of communication (because that would spoil the fun), I will however point out some aspects, or moments, just for the sake of clarification, and to be able to discuss the “satire” dimension of the movie. Take, for example, the “fire brigade” – which works as a perfect metaphor for the “Communist Party”; starting from the casting, with the “president” of the brigade looking exactly like a Party Leader from any Central or Eastern European Communist country; to the very modus operandi of said brigade: secretive, behind closed doors, and more concerned with appearances, than with true achievements; referring to “the people” as a “them”. vs ”us”; and always making sure, without daring to admit it, that they collect the material spoils; but being keen on maintaining the appearances, for example by organizing a ball “for the people”, and also an “official ceremony” for a “respected” (but in fact ignored and neglected) former “president” of the brigade; and clumsy and incompetent and haphazard in all that they actually do, as it always happens, in such party-states; and abusive and exploitative toward the public, in fact, as evidenced by how they “recruit” (or, rather, “snatch”) the girls for the beauty pageant etc. I remember how, after watching Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (

I remember how, after watching Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (

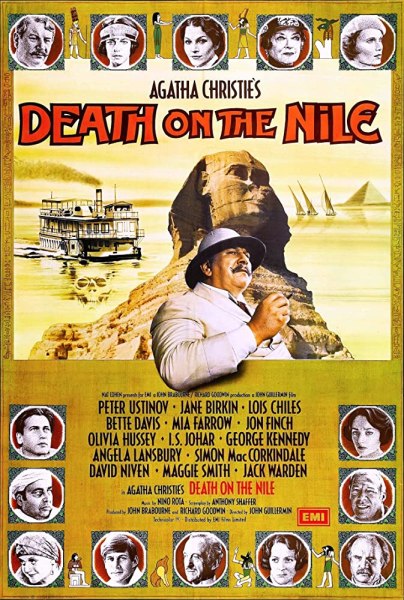

Death on the Nile (

Death on the Nile ( Speaking of all-star casts and “classic movie types”, The Sea Wolves (

Speaking of all-star casts and “classic movie types”, The Sea Wolves ( If you watch the movie shortly after reading

If you watch the movie shortly after reading  I must confess that I found it quite irritating to see how many of those end-of-the-year, “worst movies of 2019” lists included 6 Underground (

I must confess that I found it quite irritating to see how many of those end-of-the-year, “worst movies of 2019” lists included 6 Underground ( Soon after beginning Terrence Malick’s newest film, A Hidden Life (

Soon after beginning Terrence Malick’s newest film, A Hidden Life ( Because, how does one get to identify oneself with characters and situations – with the story – in a movie? Since we spectators are not actually there and then, we need to do it vicariously – and that happens when we, spectators, allow ourselves to become enmeshed in a given emotional, human situation; when we feel that it is us who are addressed by a character, in a dialogue – and we instinctively react to that, emotionally – and then compare our own reactions to that of the character addressed in the movie. In other words, it is through vicariously lived (“real” – that is, flowing, dynamic) human interactions that we are drawn in, into the given drama. And this is why it seems to me that this strange editing technique, by fragmenting and by making the characters’ interactions impersonal – also leaves us, to a good degree, emotionally outside – and contributes to the general feeling of “impersonality”.

Because, how does one get to identify oneself with characters and situations – with the story – in a movie? Since we spectators are not actually there and then, we need to do it vicariously – and that happens when we, spectators, allow ourselves to become enmeshed in a given emotional, human situation; when we feel that it is us who are addressed by a character, in a dialogue – and we instinctively react to that, emotionally – and then compare our own reactions to that of the character addressed in the movie. In other words, it is through vicariously lived (“real” – that is, flowing, dynamic) human interactions that we are drawn in, into the given drama. And this is why it seems to me that this strange editing technique, by fragmenting and by making the characters’ interactions impersonal – also leaves us, to a good degree, emotionally outside – and contributes to the general feeling of “impersonality”. The reason why The Mandalorian (

The reason why The Mandalorian ( I guess that, for many, Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (

I guess that, for many, Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman ( I have seen Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (

I have seen Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal ( These being said (and we did just say a lot), let’s continue with our overview of the main characters of the film – and the next one in that review would be the character of Death itself, whose interaction with the knight Block (which begins at the very beginning of the movie) provides the framework and the interlude within which the entire action of the film takes place. (By the way, Block’s game of chess with Death, which starts at the beginning of the movie, and give the context for the movie, might just be a metaphor – for the movie, for the quest, and even for life itself… but, truly, enough with the metaphors!) Well, this “Death” fellow makes for a strange character. Not because it is “Death”; no, but because of the peculiar characteristics exhibited by this “character” in this work of art. For example, Death professes to be “unknowing” itself (!), and thus to not be able to say anything about the “after-life.” Well, normally, if “anyone” or anything should be able to say something about the after-life, that would be Death! So, what does this mean? Well, it seems that in this movie this character of Death is presented – and is seen – quite narrowly; that is, only through the perspective of what Bergman (and us, general humankind) knows for sure about “death”. And, what do we know for sure? well, mostly, we know it as a limit – universal, ineluctable, immutable, coming-for-everyone – but a limit is most or all that everybody knows for certain about Death. And therein lies the problem – that, if this is all that we, spectators, the general public, know about a character, it is not also what the character itself – what Death – would know about itself! In other words, it is strange the character of Death is presented through this, as it were, foreshortened perspective, being limited (as a character!) by our existing knowledge of it; when, in fact, Death should be the very character that would bring us new information – both about itself, and about what follows thereafter. (And this as well serve as the beginning of an explanation for why I was unsatisfied with the movie, and that dance macabre that concluded it.)

These being said (and we did just say a lot), let’s continue with our overview of the main characters of the film – and the next one in that review would be the character of Death itself, whose interaction with the knight Block (which begins at the very beginning of the movie) provides the framework and the interlude within which the entire action of the film takes place. (By the way, Block’s game of chess with Death, which starts at the beginning of the movie, and give the context for the movie, might just be a metaphor – for the movie, for the quest, and even for life itself… but, truly, enough with the metaphors!) Well, this “Death” fellow makes for a strange character. Not because it is “Death”; no, but because of the peculiar characteristics exhibited by this “character” in this work of art. For example, Death professes to be “unknowing” itself (!), and thus to not be able to say anything about the “after-life.” Well, normally, if “anyone” or anything should be able to say something about the after-life, that would be Death! So, what does this mean? Well, it seems that in this movie this character of Death is presented – and is seen – quite narrowly; that is, only through the perspective of what Bergman (and us, general humankind) knows for sure about “death”. And, what do we know for sure? well, mostly, we know it as a limit – universal, ineluctable, immutable, coming-for-everyone – but a limit is most or all that everybody knows for certain about Death. And therein lies the problem – that, if this is all that we, spectators, the general public, know about a character, it is not also what the character itself – what Death – would know about itself! In other words, it is strange the character of Death is presented through this, as it were, foreshortened perspective, being limited (as a character!) by our existing knowledge of it; when, in fact, Death should be the very character that would bring us new information – both about itself, and about what follows thereafter. (And this as well serve as the beginning of an explanation for why I was unsatisfied with the movie, and that dance macabre that concluded it.) Tommy Wirkola’s two movies, Dead Snow (

Tommy Wirkola’s two movies, Dead Snow ( It is not by chance, then, that Dead Snow makes reference, both textually and filmically, to those movies. However, these are not some Evil Dead “wannabes”; no, these are original works, while also being fully aware of the cinematic universe that preceded and that surrounds them (and not only within the genre; thus, in DS 1 one of the characters is a cinephile who often references or quotes from other movies; while in DS 2 the clash between the Nazi zombies and the Soviet ones is informed, visually, by the choreography of the battle scenes from Braveheart – for example).

It is not by chance, then, that Dead Snow makes reference, both textually and filmically, to those movies. However, these are not some Evil Dead “wannabes”; no, these are original works, while also being fully aware of the cinematic universe that preceded and that surrounds them (and not only within the genre; thus, in DS 1 one of the characters is a cinephile who often references or quotes from other movies; while in DS 2 the clash between the Nazi zombies and the Soviet ones is informed, visually, by the choreography of the battle scenes from Braveheart – for example).