one of the great comedies in cinema history / on art vs. ideology

Miloš Forman’s The Firemen’s Ball (synopsis; clip; cast & crew; rating) is a great comedy, which works on several levels: as a direct, accessible, “popular” piece – and as a satire on the (ideological-totalitarian) Communist regime of Czechoslovakia (of 1967). And, while it works very well on the first level, and while one can learn a lot from it about comedy-making, in general, it is the second aspect that elevates it to the level of greatness – indeed, (for me) to being one of the great comedies of the history of cinema. However, it is on this very account (i.e. given the artistic richness that arises precisely from its nature as a satire on an ideological-totalitarian regime) that one wonders whether a specific “experiential” background (namely having personally experienced, or knowing indirectly about, life under ideological-totalitarian regimes) might not be needed in order to fully and thoroughly enjoy all the comedic dimensions of this film.

Miloš Forman’s The Firemen’s Ball (synopsis; clip; cast & crew; rating) is a great comedy, which works on several levels: as a direct, accessible, “popular” piece – and as a satire on the (ideological-totalitarian) Communist regime of Czechoslovakia (of 1967). And, while it works very well on the first level, and while one can learn a lot from it about comedy-making, in general, it is the second aspect that elevates it to the level of greatness – indeed, (for me) to being one of the great comedies of the history of cinema. However, it is on this very account (i.e. given the artistic richness that arises precisely from its nature as a satire on an ideological-totalitarian regime) that one wonders whether a specific “experiential” background (namely having personally experienced, or knowing indirectly about, life under ideological-totalitarian regimes) might not be needed in order to fully and thoroughly enjoy all the comedic dimensions of this film.

At the same time, however, we ourselves are also living during highly ideologized times (and things seem to only be getting worse, in that regard); so, sooner or later today’s artists might also have to learn how to speak the special language of hints, allusions, and allegories – which is the language that all artists who tried to remain truthful to art itself had to learn how to speak, under ideological (e.g. Communist) regimes – and which is the satirical language of The Firemen’s Ball. So, as said, there is a lot to learn from this movie – both about how to make a swift, funny, and universally-accessible comedy, and also about how to create art (and how to make humor) in times of ideology. But these are the very reasons why I thought that this would be a timely movie – to re-watch and to discuss.

But let us start with the general, universally-accessible “comedy” dimension of the movie – and in that sense let us appreciate the swift and light-footed pacing of the movie, as befits a good comedy, or a farce. Let us also mention here (because it has to be mentioned) the ever-so-slightly bawdy, even libertine, humor (and spirit) characterizing Forman’s works (see also the films that he made after emigrating to the US), a style and tradition of humor that I would call specifically Bohemian (as in, pertaining to a specific strand in the cultural history of Bohemia / today’s Czechia). Indeed, going back to (for example) Jaroslav Hašek – and to other artists as well, of course – one will observe a certain shared language and attitude, which one could call very worldly (or very secularized), and which is also peppered with accents ranging from bawdy to rowdy; but which is also, and at the same time, lighthearted; and universally mocking; and somewhat cynical; and also light, and playful (a language and attitude which might go back to the experience of the religious wars of Bohemia, and the resulting, generally disabused attitude toward religion, and toward all “hard rules”; see also the fact that Czechia today is one of the most a-religious countries in the world). And yet, let us not get bogged down by epithets that might sound too sour and dour; because, from Hašek to Forman, this is also the language of what one might call (with another famous Czech author, Milan Kundera) of “the lightness of being” (and yet, contra Kundera, not “unbearable”, but making existence bearable, by mocking its self-seriousness). So, overall, quite a “human”, even humanistic – and also quite enjoyable – artistic attitude (Hašek, for example, uses this attitude and this kind of language to counterpose the needs and requirements of basic human life, to the absurdity of war).

So this is a comedy that works on several levels – one using a comedic language of Laurel and Hardy-esque simplicity and universality, and the other functioning as a satire poking fun at the ideological regime (i.e. at “them”) – and also at ourselves, at us all. And, regarding this last item, there is indeed a kind of deep humanity (or humanism) in this capacity to see the comedic in our very condition, in our everydayness, in our failings – in our both incredibly annoying, but also somehow endearing, quotidian humanness and fallibility.

And at this point another aspect would need to be discussed, as well – in order to be able to make sense of the “satire” dimension of the movie; namely, the issue of art vs. ideology. To give a bit of context: this movie was made at a time of relative “thawing”, during the (otherwise oppressive) times of Communist rule in Czechoslovakia; a period of “thawing”, then, during which a kind of “Communism with a human face” (i.e. a more “humane” ideological regime) was attempted, and was still thought possible. The problem, though, with such attempts at “relaxing” regimes based on coercion and control is that, once you crack open the door of the totalitarian system, just a bit, and once you allow a little freedom, a tsunami of free expression will immediately form and try to get through; and, unless you bolt the door again, quickly, through coercion and violence (as it happened in Czechoslovakia in 1968, not long after the making of this movie – when Soviet and Warsaw Pact troops invaded the country, to end this attempt at a “thawing”), that tsunami of “free expression” might end up washing away the very regime (as it happened, at the end of the 1980s, in the USSR, after Gorbachev’s attempts at a kind of “thawing” – at glasnost and perestroika). One should also mention here, just as a bit of context, that the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia was forcibly imposed on that country, under pressure from the “liberating” USSR troops, at the end of WWII; and that, while Czechoslovakia remained a “sovereign” country, it also kept that Communist regime, under the imminent threat of Soviet intervention; and that the Communist regime lasted in Czechoslovakia, as many of you might know, until 1989. Remember, then, in this context, that this movie was made in… 1967.

But, getting back to the issue of art versus ideology – let us begin the discussion by clarifying that for ideological regimes, art is always one of the first targets that they want to take over and control. Without going into too much detail, let us just say that the reason why this happens is that ideologies, being universal and exclusive meta-narratives, which claim to both explain and to fix the world itself, and the entirety of existence, can not bear having to compete with alternate narratives (stories) about reality. At the same time, what is art but a reflection – or narrative – about reality; and what is true art (at least in my conception), but a truthful and poignant reflection of the truth of existence, and of the human condition. However, and as said, ideologies can not bear this – can not bear the existence of competing, even contrary narratives; which is why they (ideologies) always try to censor and to control art, by “cutting out” and “purifying” it of all content that is deemed contrary to the ideological narrative. Of course, once “art” is thus controlled, censored, and “purified”, it ceases actually being art – which is also why “ideological art” always comes across as fake, inauthentic, risible (see “propaganda”; or see the artistic direction that used to be called “Socialist Realism” etc.).

Which is why the true artist, when working during ideological times or under ideological regimes, in order to still be able to create and to express himself, will only have a few choices of action at his disposal: to “write for the drawer” (i.e. to work in secret, without hope of being published in the here and now); to compromise with the regime (or even to become its obedient mouthpiece – in which case art, of course, ceases); or to develop and use (and here we get to The Firemen’s Ball) a specific language of hints and allegories, which will allow for one’s works to still be published, and which the public will recognize and understand, but which the censors will try hard to suppress, albeit encountering difficulties in this process, given its indirectness (although they did ban Forman’s movie, eventually); or simply to leave (to emigrate; which eventually Forman had to do). This movie, then, is an example (and exemplar) of how to do satire on ideological regimes, while living within such an ideological regime – an example that has perfected said language of allusions, hints and metaphors, through which one can say poignant and recognizable things, without spelling them out (and risking losing access to the public).

Without going into too much detail about the specific ways in which the movie achieves this type of communication (because that would spoil the fun), I will however point out some aspects, or moments, just for the sake of clarification, and to be able to discuss the “satire” dimension of the movie. Take, for example, the “fire brigade” – which works as a perfect metaphor for the “Communist Party”; starting from the casting, with the “president” of the brigade looking exactly like a Party Leader from any Central or Eastern European Communist country; to the very modus operandi of said brigade: secretive, behind closed doors, and more concerned with appearances, than with true achievements; referring to “the people” as a “them”. vs ”us”; and always making sure, without daring to admit it, that they collect the material spoils; but being keen on maintaining the appearances, for example by organizing a ball “for the people”, and also an “official ceremony” for a “respected” (but in fact ignored and neglected) former “president” of the brigade; and clumsy and incompetent and haphazard in all that they actually do, as it always happens, in such party-states; and abusive and exploitative toward the public, in fact, as evidenced by how they “recruit” (or, rather, “snatch”) the girls for the beauty pageant etc.

Without going into too much detail about the specific ways in which the movie achieves this type of communication (because that would spoil the fun), I will however point out some aspects, or moments, just for the sake of clarification, and to be able to discuss the “satire” dimension of the movie. Take, for example, the “fire brigade” – which works as a perfect metaphor for the “Communist Party”; starting from the casting, with the “president” of the brigade looking exactly like a Party Leader from any Central or Eastern European Communist country; to the very modus operandi of said brigade: secretive, behind closed doors, and more concerned with appearances, than with true achievements; referring to “the people” as a “them”. vs ”us”; and always making sure, without daring to admit it, that they collect the material spoils; but being keen on maintaining the appearances, for example by organizing a ball “for the people”, and also an “official ceremony” for a “respected” (but in fact ignored and neglected) former “president” of the brigade; and clumsy and incompetent and haphazard in all that they actually do, as it always happens, in such party-states; and abusive and exploitative toward the public, in fact, as evidenced by how they “recruit” (or, rather, “snatch”) the girls for the beauty pageant etc.

But, as mentioned above, and in line with the Bohemian artistic tradition I mentioned, the satire is not directed only at “them” (at the regime) – but also at “us”, at “the people”; because it would be just as hypocritical (as the Party itself is) not to admit that we, too, are also complicit in the system (as another Czech, Vaclav Havel, explained it in his famous essay, The Power of the Powerless) – as without our silent acceptance, or complacency, the regime and its veil of lies would not survive. Thus, in the movie (and quite hilariously) the people partake equally in “the game of appearances and of spoils-getting”, in which the Party )sorry: fire brigade) is also engaged. And this, by the way, is a very accurate reflection of what happens in all ideological regimes, after the initial – and most bloody – period of ideological-revolutionary fervor; namely, that there comes always a period of “settling down”, of a mutually and silently accepted status quo, within which “we pretend that we do not know that they are lying, and that they are out to get their spoils; while they pretend that they believe the we believe them, and try to ignore our own spoils-getting”. A generalized lie, and a merry-go-round of foolery – indeed, but do not forget that the first requirement and demand of life is simply to survive – and most human beings will first of all try to do that; so, “spoils-getting”, perhaps, but that can also be just another name for “the people” doing their best to simply live (survive). Yet this is what great satire does – it penetrates through the veil of appearances, to reveal the truth – and points out both that the emperor is naked (and he is, and most egregiously so) – but also that we ourselves have holes in the bottoms of our pants, as well. And when satire reaches this level of poignant and expressive truth telling, it becomes true and high art (not art with a message – but art as truthful depiction of existence, and of the human condition).

And there are some genuinely laugh-out-loud moments of this kind – of anti-ideological satire – in the movie; that is, moments in which the truth, reality, penetrate through the cracks in the carefully-painted façade; and our laughter comes both from recognizing both the accurate depiction of the ridiculous “façade” that such a regime puts up, and from the contrast between these appearances, and the actual truth of existence, as we know it from our daily experience. Examples of such moments are, for example, the scenes with the one “honest” fireman (and with his wife…) “guarding” the table with the tombola prizes; or when the lights are switched off, so that “the people” can return the prizes that were stolen; and, of course, the scene with the conferring of the “award” on the former president of the fire brigade (who, by the way, comes across like one of those old-guard, true-red, first- generation Commies – who is now stored away, and forgotten, being dragged out only for meaningless ceremonies). Ah, all the hypocrisy, the make-belief, the incompetence, and the generalized profiteering that always – always and without fail! – become the characteristics of ideological regimes – and that constitute such rich fodder for satire!

But there are also some more serious, even moving, moments, in the film (not gloomy, but serious in their humanity) – moments when the “carnival ride” grinds to a close, and the tragic dimension of existence (and of life under such regimes) comes through. Examples would include, of course, the scenes with the old man’s house catching fire, and what happens (with him and with the house) afterward. Indeed – even while instances of pettiness and “small-mindedness” abound even in these scenes (like the buffet manager making sure that they continue to sell drinks, even to the people gathered around the house fire) – there are also some solemn, even spiritual moments; like, for example, when the crowd starts intoning a song, while keeping a sort of vigil around the fire; or with the old man reciting, while watching his whole life burn down, a stammered, half-remembered, “Our Father”. And there should be such moments, as well – because human existence is also tragic – and because underneath this typical Bohemian humor there is also a sense of the “tragedy of existence”.

But at this point the same concern that I stated earlier comes to mind – namely, about the ability of the “average” Western viewer (who has not experienced, or who has not realized that he has experienced, life under ideological regimes) to “recognize” and to “perceive” this satirical (anti-ideological) language. Of course, anyone who is not familiar with the existential experience of living under ideological regimes, can easily address that – and I am thinking of the quasi-experiential means of movies and books on the subject (and there are so many of them; from, for example, Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago, which itself is pervaded by irony, and thus by dark humor – to, for example, a more recent movie like Tales from the Golden Age etc.).

At the same time, I also wonder if said Western viewer should not actually be in a hurry to do so – to familiarize himself with the nature of ideologies, and of ideological regimes; and, as a corollary, with the means of (still) making (and consuming) art under such regimes. I say this because, as mentioned before, we do live during highly ideologized times – and the situation, far from relenting, seems to be only intensifying. And one needs to remember that under such conditions – namely, if the false narrative of ideology takes over – the challenge, both for the artist and for the public, will be to learn how to still hold on to what they know to be the truth – and reject the falsity of ideology – while still “surviving”, if possible (still having a job, or even surviving physically). As discussed, there are only a few options available for the artist (and for the public, in fact), in such conditions: (1) compromise, or even active collaboration; (2) resignation to being “cancelled” or “deplatformed”, and to making art “for one’s drawer”, with the hope for a possible future audience; (3) developing a special, subversive artistic language, that can still get published, but which tries to still speak the truth, through hints and allusions; (4) or exile.

And, remember, ideological regimes come in many shapes and forms, in that the false narrative of ideology can be imposed through various means, whether hard (the brute power and institutions of the state) or soft (cancellation; ostracism; peer or crowd pressure; economic pressure etc.). And this is why it is important to remember, especially in such soft-totalitarian contexts (in which the frog is more easily boiled), that the first and foremost duty of the artist (and of every human being with a conscience) is to have the internal courage and awareness to hang on to what they know to be the truth – and to trust that what feels hypocritical and false, is actually so (no matter the moral pretenses or apparent motivations of the ideological narrative). In other words, for such satire (and for such a language of metaphors and allusions) to work, both the artist and (a part of) the public need to still be able to hang on to – and thus to internally recognize – the truth. And there will always be people who can still recognize the truth; because ideologies can do many things (through coercion and violence) – but they can not change the truth.

To conclude, The Firemen’s Ball is a thoroughly enjoyable and hilarious film – which works both as a general, universally-accessible comedy – and as an existentially reinvigorating satire on ideological regimes. And this is why (today’s) artists and filmmakers can learn a lot from it – on both accounts.

I remember how, after watching Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (

I remember how, after watching Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (

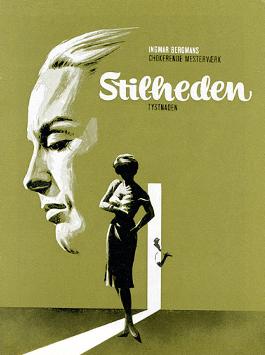

Together with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light, The Silence (

Together with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light, The Silence (