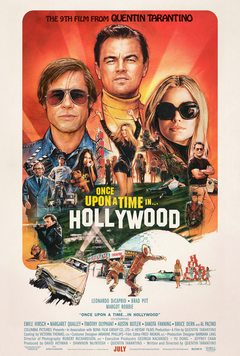

“grand cinema – and an ode to classic Hollywood”

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood (synopsis, trailer, cast & crew, rating) is a most pleasurable fare; it might just be my favorite Tarantino movie, or at least ranking at the same level as Pulp Fiction (or Reservoir Dogs), while being quite different from those. But what makes it so appealing?

First of all, its atmosphere. Clearly the intention was to capture and to reproduce a specific time and place: the classic Hollywood of the 1960s (the end of an era, and the transition into a new era – from the TV and films of the 50s and of the 60s, into the culturally very different decades of the 70s – and of the 80s). In the process of reconstructing this world – which Tarantino does, clearly, with care and affection – the movie also reproduces what could be best expressed as “Americana” – or, “Californiana” (for many around the world, the image of California, especially as learned from the movies, is emblematic for what and how the US is supposed to be). It is a sunny, affectionate, but also in many ways blunt reproduction of a world (or of several worlds: of movie and TV production, of working actors, of “civilians” living in Hollywood, of rich people, and of decrepit people). But it all revolves, of course, around the world of film, of movie-making.

That, indeed, is the center of Hollywood (or used to be), so we encounter and see people living at various degrees of closeness or distance from that center: from the up-and-coming starlet (Sharon Tate); to the actor anxiously negotiating the transition of the industry, and of himself, from the 60s into the 70s, who is worried about his future (Rick Dalton); to the crew (stuntman Cliff Booth, who lives “around” Dalton); to the child actress who exhibits an endearing seriousness about the craft, but also an understandable naivety about the working life of an actor; and even to the young girls of the hippy/cult commune of Charles Manson (who live from the crumbs of Hollywood, literally and figuratively, as they take tourists to famous people’s houses, and also pick through garbage containers). In the middle of the narrative, traversing it and giving it direction, are the two parallel stories of Dalton and of Tate (who also “happen” to be neighbors) – which is a good vehicle to showing us the everydays of the actors’ lives – their highs, and their lows; from partying, to doubt and agony about their career or their craft; from being on the way up, to being – or being afraid of being – on the way out etc. One could (and probably should) also add here the Booth storyline – but one can also qualify it as a “satellite” narrative, around and along that of Dalton.

(Speaking of Cliff Booth, and of living on the fringes of Hollywood, it is symbolic how Booth, who is formally Dalton’s stuntman and double, but nowadays works for him as his daily factotum and amigo, and who thus spends his days within the gravitational pull of Rick’s career and life – how he at night goes home to a trailer parked somewhere on a lot behind an open air cinema.)

And this Hollywood – and, in fact, this entire world – is depicted as having two opposite but complementary sides: the glamorous, seductive, fleetingly attractive one, and the dark, dangerous one, of human misery, of evil. This duality characterizes the entire movie – see the apparently fresh young things of the hippy / cult commune (e.g. Pussycat): at first sight alluring and attractive, with the promise of youth and beauty, and quickly turning into something much more dubious, ugly, scary even (the scene of Pussycat climbing unto that car and yelling and gesturing at Booth, after having been so friendly and behaving even childishly toward him, is a perfect expression of that flip of a coin; or see the appallingly dirty, unkept conditions inside Spahn’s home; not to mention the really troubling scenes at the end, when these “freedom-and-lovey” hippies are getting ready to kill.)

(As a side-note, this is the same duality that one sees and perceives in Vegas, or in Atlantic City – one just has to step off the main strip, to see the undergirth, the seamy underbelly, of the glittering surface; all those “occupations” and endeavors that grow like a dark fungus around and under money, fame, appearances.)

But back to our initial question – why did I find this movie attractive, pleasurable? Besides the atmosphere (the Hollywood of the 60s), which is so well captured, the film is also very well (and thus enjoyably) structured. As said, the main thread goes along two (three) parallel narratives, of Dalton (and Booth) and of Tate, and that constitutes, as it were, the middle of the movie; which is preceded by an aesthetic-emotional and informative introduction into the world and the momentary status of each of these characters; and is followed and concluded by a coda about their paths, which itself ends with an egregious (but also egregiously enjoyable) finale.

Speaking of the finale – when I first saw the movie, the ending was definitely not what, or how, I expected it to be. Not having read much about the details of the plot of this movie (I never do), I still knew that it featured or made reference to Sharon Tate (who, as is well known, was brutally murdered – in real life – by Manson’s followers). Knowing that much about the movie, while I was watching it for the first time I kept getting tense and nervous, at various moments throughout the film, when I expected – every moment now! – for something bad to happen, for violence to erupt; in a way, the threat of evil hung above the movie throughout, during the first watching (such a tense, expectant moment in the movie was when Booth visited the hippy/Manson farm). And yet, nothing happens… well, not until the end.

Speaking of the ending, then, I must say that, when I first watched the movie, I found it somewhat disappointing, or underwhelming, simply because I could not make sense of why Tarantino had chosen to deviate from the historical facts. I simply could not understand the reasoning behind the choice (although one could say that it is a metaphor for Tarantino “saving” that classical Hollywood that he lovingly recreates and displays in this movie – but I am not terribly interested in metaphorical explanations.) When watching the movie the second time, however, since I no longer expected that the actual, historically accurate story of Sharon Tate would be depicted (at least in its actual denouement), and since I was thus freed from the ongoing tension of not knowing when evil would break through, and when violence would erupt, I was also able to watch the ending in a more detached state, and to find satisfaction in it. Mind you, even when watching it the first time, I found that concluding festival of violence (oddly) satisfying and rewarding (perhaps also as a much deserved comeuppance for those evil hippy/cult members).

Except, perhaps, for that rather prolonged shot of the carbonized body of the woman in the pool – and not because I was in any way repulsed by that image – by no means; to the contrary, I found that lingering on it actually took away from the “realism,” and thus from the impact, of those scenes of violence. and that it took us out of the moment, at least to a degree. And this takes us to another aspect that I would like to note, regarding this movie – namely, a certain degree (or a streak) of self-indulgence, which I have noticed in other Tarantino films, as well, after the great successes with Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction; and which I also noticed, for example, in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, as well (another great movie, by the way). What is all this about? Well, it seems that once the “general verdict” about a director (or about an artist, in general) is that they are a “genius,” or something “extraordinary” – and once, as a result of that, they are put on a sort of pedestal, being given (to a large degree) free rein, and being thus excluded or sheltered from the grind of the daily negotiations with the studio or with the producers, or from having to cope with very tight limits of time and budget – it seems that, once all these happen, what also comes with this is a certain slackening of artistic self-discipline, on the part of said artist.

This can manifest itself in various ways – for example, in this movie I would classify under such a heading the random use of indicative or explanatory text on the screen – random, because it happens in fact only two times: in the scene with Steve McQueen, at the party, and in the one with the car jumping between the two elevated ends of a bridge, while filming that Italian mock-Bond movie. Now, why use these superscripts? Why introduce them, randomly, and only in those two moments? In other words, if the use of such text would be an integral part of the “language” and visual style of this movie (like, for example, the trippy multicolored images interspersed in Punch Drunk Love, or the silent film-like intertitles in The Sensation of Sight), then nobody would mind; but doing something just because one is able to do, even if it comes across as incongruous with the overall tone or style of the movie – well, that I would classify as self-indulgent.

But this is not a new issue, or question, for art and the artists; namely, what is best, for the artist to have complete free rein, or for him to have to deal, and thus to enter into a conversation, with certain limits (which can be limits of style, as in certain “formal rules;” or of means at one’s disposal, or of time etc.). There is the Romantic (uppercase, as in the historical current) notion of the artist soaring unencumbered, as being the best and most desirable state and condition, as he then can attain to the highest realms of aesthetics and of truth. Appealing image, which is also related to another underlying modern idea, that freedom is a value in itself – instead of being only a condition, that gives us the possibility of choice – a choice that can be good, bad, at least imperfect etc. After all, in this very movie aren’t the young hippies of the Manson commune “free,” practicing free living and free loving – and yet their “free choice” turns out to be for deepest, darkest evil?

Without going too far away from our discussion of the movie, one should remember that all (or at least, the overwhelming majority) of Michelangelo Buonarotti’s works were commissions – where he was given a clear task, a certain “surface” or location, and a fairly clear commission – within which he then was able to manifest his soaring creativity and, in fact, genius. But am I arguing for the necessity of outer constraints, of having to fight with obtuse studio executives, and so on? No, never. But I am arguing for the necessity of inner constraints, by which I simply mean an inner artistic discipline, which translates into a certain unity of style, into a coherent artistic language. And sometimes the need to engage a fixed outer framework (necessities and constraints) – be it only in terms of money and of time – helps develop that internal discipline, which results in a more aesthetically balanced and harmonious artistic act. In other words, just because one may use free rhyme (which I actually prefer, or at least I delight in), does not mean that, automatically, his poems will actually have a higher artistic value.

But back to our movie; other instances which I would identify as manifestations of a similar lack of aesthetic self-discipline (i.e. coherence), would be, for example, the overly long scene of Dalton filming a Western; the same thing could have been achieved in a much more concentrated and focused (yet not rushed) manner. Or even the fact that Kurt Russell (who also plays a character in the movie) narrates, here and there, parts of the movie; why Russell? Clearly, it is not the character whom he plays in the movie who actually does the narrating – or is it? So why confuse the planes? And why narrate only at certain (random?) moments, and not more consistently, throughout the film? Again, this – and similar instances – feel like moments of decision which went broadly along the lines of “I can do it, so I’ll do it.” And this is where the studio guy (not that I like them, or want them to meddle – but just as an example) would come in at the end of the day, see the rushes (or check later on the editing process), and ask – why? Or someone, anyone, would ask, why?

Because another problem with artists being put on a pedestal, and receiving, as it were, a sort of a carte blanche, is that the critics as well tend to be possessed by a sort of a feeling of inferiority toward these declared geniuses, so that when they see something that they do not understand, they feel that it is probably their fault (or at least, that it is gauche) that they do not understand, and thus will not question the artist’s choice (and thus would not begin a dialogue that might just help clarify and thus elevate the artist’s own craft). (Not that I am on the “side” of the critics, generally speaking; if anything, you will find me on the side of the artist, most of the time, almost always; but this is a question, as said, of actually helping the artist develop and practice a coherent aesthetics – which is what, I guess, I am half-reproaching, or at least bringing up, when talking about this so-called self-indulgent moments, in the later works of people like Tarantino or Scorsese). But enough of this: I did not bring up these aspects because they would be crucially important aspects of the film – in fact, these are relatively minor, and clearly not decisive, details; I just enjoy such occasions of picking up on issues that can then lead to broader discussions about the condition and the craft of the artist; so this is what this was, a useful divagation – accompanied by a relatively small criticism.

But speaking of criticisms – another aspect that I did not fully understand, nor entirely appreciate – was the way in which scenes from movies and TV shows “of the 60s” (real or imagined) were (re)created and integrated in this movie. First of all, Tarantino used a variety of means for doing that – he either shot a whole scene (or set of scenes) for an imaginary 60s TV show, or he used CGI to replace the original actor with DiCaprio, within real footage from a real ‘60s film. However, the quality (or the style) of these efforts was uneven – compare the less-than-convincing footage with DiCaprio in The Great Escape, replacing Steve McQueen, with that of Leo in the FBI TV show (of course, this might be a conscious choice, as the first one was Dalton imagining himself playing the role in The Great Escape, while the second was a show in which Dalton “actually appeared”). But, more importantly, I would mention here the different “western TV show” scenes filmed by Tarantino, which did not come across as entirely veracious, for me, not because of anything having to do with the set design or other externalities (of course not), but mostly because the actors themselves did not behave (read: act) in that same mannered, formalized, even somehow uncanny way that was characteristic for the acting style of that age, in those movies and TV shows. My point here is not about “mistakes” or “faults” – but about questioning the reasoning behind these choices. In other words, if Tarantino wanted to actually recreate (“with his own hands”) mock-60s westerns – then do it all the way, paying attention to every little detail, and being faithful to a T! And, if you want to insert current actors into old footage – then do it in the same way, whether ultra-realistically, or with some inherent awkwardness – it does not matter, but let the efforts be coherent. Otherwise, I simply do not understand these variations in approach or quality – are they accidental, or are they intended – and, if so, why? I guess that the issue here is not about the actual choice – of doing it this way, or that way; but, again, of using a coherent and unified style and cinematic “language.”

But, although I seem to have spent long paragraphs on these “qualms” – these are, in fact, minor issues, which I see worthy of discussing only (or mostly) because they allow me to raise broader questions of aesthetics and style. Overall, these do not affect in a notable way the overwhelmingly positive qualities of this movie.

And now on to the next issue – let’s talk a bit about the acting in this movie. I must confess that I found Leo DiCaprio’s work in this movie quite excellent, as he created a character – and embodied a person – that was truly different: somewhat rough, and somewhat of a simpleton; anxious, but also arrogant; rich but afraid – it was all good. Margot Robbie as Sharon Tate was exquisitely delightful, as well – a masterclass in showing that you do not need to talk, in order to act – what you need to do is be; yes, most enjoyable. And this takes us to Brad Pitt – who has recently received several accolades (awards) for his work in this movie, but by whose performance I must confess that I was in no way impressed. Not that he did anything wrong – to the contrary, he carried the role very well, did a perfectly fine job; but, for me, nothing that he did was in any remarkable way different or “other” from previous Brad Pitt characters and personae. This is why I emphasized the fact that DiCaprio embodied a character who was markedly different – both from him, and from his previous roles (in my estimation). For me, DiCaprio was the stand-out – and Robbie – in a field of otherwise uniformly superior performances (including that of Brad Pitt). I just don’t see why all the accolades (unless they were conferred for his overall acting career – as it often happens). Finally, it was also good to see Al Pacino doing a very different character himself (a small-ish, but impactful and delightful part); and I also found the presence of, and the scenes with, “Bruce Lee” (played by Mike Moh), funny and refreshing.

Speaking of Bruce Lee, in the tagline to this discussion I mentioned that this film is “an ode to classic Hollywood;” yes, but in a broad sense – that includes movie-making, but also the TV shows of the 50s and the 60s; and the (then) newly-arrived Asian martial arts genre; and the fascinating world of Italian spaghetti westerns (and spaghetti movies in general). All these styles and “worlds” have been, of course, perennial points of reference and personal favorites of Tarantino himself… And this is how and why this film is quite the personal paean to movies – to cinema – to the medium and world of film, itself. An imaginary story about a medium that is, essentially, imagination made visible and real.

I also mentioned earlier that this movie has become one of my favorites – if not my absolute favorite – of Tarantino’s body of work. I am using the word ”favorite” consciously, because it implies a subjective relationship with the movie – which would be accurate, as I find myself “liking’ this movie, in the sense of a personal attraction and enjoyment which is not the same with the somewhat cooler (in both senses) and more intellectual enjoyment of (and admiration for) Pulp Fiction (or Reservoir Dogs). In other words, this movie appeals to my aesthetic and personal leanings, in ways in which the other two do not. And why is that? Well, perhaps because of the actual world it describes – of the classic America of the 60s and 70s; of sunny California – that is, Hollywood etc. It turns out that I might have if not similar, then at least parallel warm feelings towards these times and images (toward this Americana), as Tarantino has. So, the coupé driving down a Hollywood boulevard, on that street lined with classic American neon signs, under a blue or dusky, ink-colored California sky, with palm trees (which, if they’re not seen, are felt) – well, aesthetically and personally, I find all this very appealing.

(We do like movies because we do like to dream. There’s an inherent romanticism – lowercase – in the medium of cinema; even if it depicts the most terrible events.)

Overall, therefore, Once Upon a Time… in Hollywood was a most pleasant experience, and a movie that I thoroughly appreciated, on several levels.

***

Footnoted minutia: for some reason (but I wonder why?) this movie was banned in China (!). Well, discuss among yourselves.

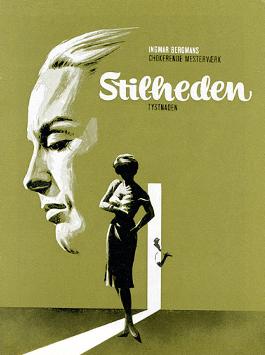

Together with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light, The Silence (

Together with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light, The Silence (

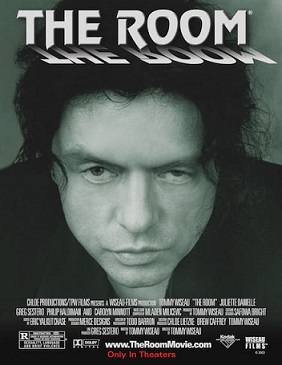

The Disaster Artist (

The Disaster Artist (