“or, the lack of communication”

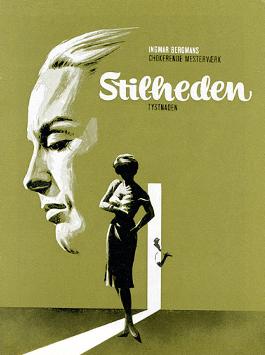

Together with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light, The Silence (synopsis, trailer, cast & crew, rating) is part of Ingmar Bergman’s trilogy dealing with (or, rather, inquiring or searching into) issues of faith and of God. Formally, this is relevant information – but we better look at the movie itself.

Together with Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light, The Silence (synopsis, trailer, cast & crew, rating) is part of Ingmar Bergman’s trilogy dealing with (or, rather, inquiring or searching into) issues of faith and of God. Formally, this is relevant information – but we better look at the movie itself.

The first question that emerges is how one should approach (or “read”) this movie. Is it a poetic, lyrical piece – in which case one lets the images and actions on the screen act upon one’s sensitivity, emotions, imagination – or is it a narrative (prose, prosaic) work, in which case one struggles to understand what exactly is happening or has happened, what are they doing and why etc. I found that for me the lyrical-poetic approach works best with this movie.

I should also note that, before watching the film, I read the script that Ingmar Bergman wrote for it (he is the writer and director of this trilogy, so these are the personal works of an auteur). Based on that, I can say that The Silence works better “as” a film, with moving images and sound, rather than as a text. I say this, because that is not necessarily the case with the other two films (and especially Through a Glass Darkly). But this movie’s title is The Silence, and it helps to be able to hear that silence – or, for example, the unintelligible noise that is a stand-in for silence, or for lack of comprehension, or for incommunicability.

Approaching then the movie as a poetic work (which means that one is less interested in what exactly took place, and when, and by whom – than in perceiving aspects and states of existence), the main impression conveyed (and perceived) is that the principal theme of the film is the lack (or even impossibility) of communication, in the broadest sense. This can be conveyed, indeed, by a noisy street, where the white noise of the daily hustle and bustle combines with the strident, cacophonic noise of the cars and of the street vendors. It can also mean actual lack of communication – or impossibility thereof – as between the two sisters (the movie’s three main characters are a younger sister and her child, and an older sister, who travel through a non-descript, foreign country, and stop at a hotel – while one of the sisters is ill, even dying). Incapacity of communication: the entire story takes place in a foreign, even alien country, whose language and habits are different and themselves “foreign”. And also to the same issue of the lack or impossibility of communication pertains the sexual behavior depicted on the screen (from vain attempts at self-love, to casual, purely physical sex. All these are examples or manifestations of said lack of communication with other human beings – and, more deeply, of a breakdown of human relationships.

And this lack of communication – “supported”, as it is. by sentiments of hatred or resentment – seems to be a symptom or manifestation of a deeper problem – of a lack of love and of faith. One of the characters had a fleeting sexual encounter (or so she says) behind the colonnades, in a church; what better image for replacing divine love with an unfruitful attempt at self-satisfaction?

(Speaking of these sexual dimensions, I noticed that for some critics or spectators this is the main, most remarked on, trait of the movie. For myself, I found that these aspects, although more directly depicted than in other movies of that era, are nevertheless filtered through an artistic lens – and, yes, it matters if one is able to take them as metaphors for something else (as I am), or simply as acts or actions. But for more info on this, see the movie’s rating.)

Lack of love, then – of affection, of relationship, of the possibility of relationship… but why? I don’t know – or, rather, Bergman hints at some of life’s obstacles to forming and keeping relationships (which I will discuss in a second) – but mostly, it seems that the underlying cause is the fact that these characters (and possibly Bergman himself, in his mid-twentieth century Sweden or Western Europe) inhabit a world that has been voided of God, faith, love, sense. An emptied world, in that sense – and yet the yearning (which is deepest in the human being) for love, remains and thus destroys (most of) these characters. But let’s not get too far off from the film itself, with our interpretations.

As said, Bergman – or, rather, his characters – hints at some of the obstacles to relationships; some of these have to do with all that accumulation of dirt, hurt, of incomprehensible inner impulses and emotions, of a relationship’s historical memory – all that is, let’s say, visceral and murky… And this takes me to one of the major strengths and points of attraction for me, with regard to Bergman’s films, which is his capacity to depict the cellular-level tissue of existence, of life – those inexpressible and un-conceptualizable strata of ourselves and of our existence that form the mundane soil of our everyday life. “Depict”, I say, because they need to be “depicted,” for example on the screen – because they cannot be “said,” expressed, through words (hence incommunicability). (But poetry is born as the artform specifically suited to express these ineffables of existence.) So these “interstices” of existence are very much present and depicted in Bergman’s films – while, at the same time, they are mostly lacking in the typical Hollywood movies (which is why, perhaps, both characters and actions in these movies tend to come across as unidimensional – because, more often than not, both characters and actions in these moves are sublimated into clear, univocal acts or traits – but that is not truthful, because we, as humans, as not unidimensional, are more complex, and not all is expressible in words; and thus we find that these movies are ultimately unsatisfying, and even feel a bit fake – unless one gets too accustomed to them).

Parenthesis: on the other hand, while this is a strength in Bergman’s movies (or so I find), and in other movies of this kind, there might also be an inherent danger in this exploration of the murky interstices of mundanity. After all, there is such a thing as a “micro infinity” – namely, dissecting physical existence into smaller and smaller sub-atomic dimensions – there is no end to that. Similarly, one could get lost – theoretically – in going deeper and deeper into the murky and confusing interstices of existence; there is that danger, as well. I am not suggesting that Bergman engages in that; I was just pondering on the right authorial strategy: without the complexity of existence, and our confusing and incomprehensible parts, life depicted appears fake; but prudence is needed, as the goal– for me – is realistic depiction of the truth of existence, and not a hubristic attempt at all-comprehension, or a wallowing in the layers of the soil of mundane life.

Another strength of Bergman’s movies (presumably related to the first) is his ability to construct and to depict real human relationships– as they are. This is why his Scenes from a Marriage (the film from 1973) is one of my favorite movies on the theme.

But back to the topic that we were discussing, of the obstacles to communication (and to relationships). Ester, the older (and ill) sister seems to refer to these accumulated obstacles, when she talks about the fact that “you need to watch your step among all the ghosts and memories”; or, talking of “[t]he forces [that] are too strong… the horrible forces”; or even of the off-putting “erections and secretions” (the viscous physicality of existence). Indeed, (helped by their acting) we perceive that in-between the sisters there is an entire past, with so many contradictory events, emotions, hurts, reactions etc., and that it is inexpressible, unclarifiable, unsolvable – and that this past is part of the reason why they can not communicate (or have a functional relationship); other reasons are implied as well. These accumulations of the past might also be responsible for the fluctuating behavior of the two women – for example, in how they relate to other people (Anna, the younger sister, alternates between being overly affectionate, or quite cold and rejective, toward her son, Johan).

We were saying that the movie is, or seems to be, about the lack of communication, and the lack of faith and of love. Let’s add here – as it is related – that in the film there is also a sense of a world that is alien, unknown/unknowable, and frightful; see the “war” themes in the movie (the trains carrying tanks, the warplanes’ flight over the city, the rumbling and then menacing apparition of a tank, on the street, in the night; the soldiers in the café – and so on); the presence of war, in other words, somberly and mutely threatening. Or the theme of the hotel, as explored by the young boy, Johan.

Here I should remark – in connection with what was said beforehand – that Bergman does a swell job in depicting the way in which a child sees or experiences the “wide world” – from the intimidating encounter with sickness or death, or with conflicts between the adults, to the incomprehensible behavior of your parent, to the strangeness of large, impersonal buildings (to be explored, but also threatening), to meeting strange strangers who speak in strange tongues about foreign things – in other words, the way in which for a child sees the things of the world of the adults, and of the world “at large,” as it were. In this movie, the child who experiences these is Johan – and his experiences represent another manifestation or expression of that incommunicability and incomprehension that I see as the central themes of the film. (And I was wondering, while watching Johan and his adventures – is this child Bergman? or is he us – versus the world? Or, even, is this a reference to some actual childhood experiences or memories of the auteur?)

There is a moment in the film when Johan, the boy, “stages” a marionette play (Punch & Judy type) for his ill aunt, Ester. It is the shortest play, because it quickly devolves into Punch “punching” Judy, while shouting incomprehensible things in a made-up language. When asked what this is about, Johan responds that Punch “is scared, so he speaks in a strange language” (and also erupts into violence toward his mate). Quite a clear hint at an interpretive key for the movie. Our existential anxiety – in a world that seems alien and emptied of meaning – also manifests itself as fear and through hurting others – and ourselves. This, of course, if this is in fact the world; but is this our world, my world? In any case, it is the world proposed and depicted by Bergman in this movie; and this might just be him pulling the alarm about, and critiquing, or even diagnosing, Western or Swedish society around the middle of the twentieth century. (But we are getting again pretty far from the film itself.)

The movie ends with Ester, the older one, drawing some conclusions about life and about herself, while she is agonizing in what is probably her deathbed (in her hotel bed). Johan and his mother, Anna, leave to continue their journey toward home, toward Sweden – but not before Ester starts writing, and then gives to Johan to take with him, a sort of embryonic “dictionary” of the language spoken in this foreign country; for example, what are their words for “hand”, “music” etc. She tells Johan – or us, the spectators, I am not sure right now – that he will discover later how important this is; this, what? Well, I assume, a dictionary means to have the words, to understand, to be able to communicate – to have a gateway into existence. Communication, as the entry point into relationships – and thus, to love and meaning (and, why not, faith).

One should also add here that the sole thing that constitutes a point of mutual comprehension and reciprocal communication between these Swedish guests and the locals (in this alien country), is music (either as Bach works played on radio, or as the words “Bach” and “music”, which turn out to be the same in both languages). Music, as an aesthetic alleviator of aloneness, alienation, incommunicability – and lack of meaning.

Yes, one could easily take this movie as a critique (or critical depiction) of a certain society – or of a certain mode of existing. Since a poem is a self-enclosed something, a universe unto itself, self-sufficient, so this movie (and films such as this) can work by depicting “one type” of world, or “one type” of existence (which might not represent the entirety of existence, or of the human possibilities). But a poem is an accentuated, hyper-sensitive depiction of one thing, of one aspect – that faces us with that aspect; in other words, most poems are not encyclopedias, intending to explain all of existence. But, by facing us with the “concentrated” version of one aspect (or type) of existence, it can force us to take it seriously, and thus to make a decision, about and for ourselves, about that specific issue. For example, we can leave this film (or the poem) with the impulse of thinking about how we can best avoid, or avoid falling into, such an empty existence – both as individuals, and as a society. A poem can thus function as a via negativa, revealing something (e.g. need for love or for meaning) by illustrating its absence. And this might be the way in which The Silence becomes part of the Bergmanian trilogy on God (or lack of, or search for God), on faith – and on existence in the 20th century.

I will conclude by saying that I am afraid that due to this discussion, and to the themes we covered, the movie might come across for you as gloomy and…; while in fact I left this film – as it usually happens with Bergman’s movies – energized and engaged; and I assume that this has to do with the cathartic effect that true artworks have on us (see the Greek tragedies’ effect on their contemporary spectators) – namely, artworks that speak to us by touching on aspects of the truth of reality, of existence; yes, there is something very rewarding and moving when one encounters real communication about real things (even if that thing is “the lack of communication in a God-less, and thus sense- and love-less, world”).

I mentioned at the beginning of this discussion (and I promise that this is its last remark) that my approach to and “reading” of this movie was poetic, lyrical; letting the images and sounds, the humans’ actions, the emotions depicted, enact their effects on my capacities of perception and feeling (just like I would do with a poem or a painting). And I think that that was a good choice, because I dare say that, taken purely prosaically, this movie would not “work” – i.e. if one would approach it very prosaically, as a puzzle to be solved (who does what, when, why, and what is the conclusion). There are too many gaps in information for the movie to work in that sense – and it would soon become frustrating, or unrealistic (un-pragmatic), in that case. And here we arrive at the criticism often raised against so-called art(sy) movies – regarding their incomprehensibility, pretentiousness, remoteness from everyday experience (and the everyday viewer). Well, if a movie is “artsy” and only artsy, (for artsiness’ sake), then I am fully on board with rejecting such snobbish and pretentious nonsense. However, in my reading, this is not that. But does it have moments when there is a slight hint at pretentiousness, at a certain abstracted mannerism? Perhaps, a few; for example, I found Gunnel Lindblom’s writhing in bed, as she was alternating between hysterical crying and manic laughter, pretentious, mannered and unnecessary.

But I am certain (and I am not the only one) that this movie is not intended simply as a pragmatic narrative – it is designed to appeal to our poetic sensibilities; it wants us to feel, to perceive, and thus to understand existentially – or, as I said, poetically. So, I left this movie engaged and replenished with thoughts and feelings about true, real, existential things – thus a rewarding experience. However, I will note that of the three films in the trilogy, Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, and The Silence – all of which I appreciate and I have enjoyed – this might be my least favorite (and yet still an engrossing and rewarding experience, and a movie that I would recommend, for those interested in such fare).